Vultures on black-fingered wings tilt back and forth over the broken trees. – Peter Matthiesen

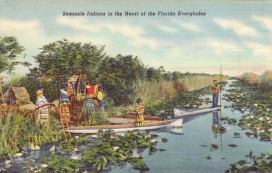

Could it be those fingers of swampy wildness that reach into the Metroplex with Saw Grass and Coontie? The whorl-shaped sloughs that surround Ft. Lauderdale airport? The drainage ditches along Route 75 or the mysterious savannah I first glimpsed through a chain-link fence on the way to Key West? Where do the Everglades begin? Sometimes, strolling through Bal Harbour, I catch a whiff of jungle funk wafting on the breeze from an outlying swale and I think of Ponce de León, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés and others who came here for conquest and glory, but only found mosquitoes, disease, and sodden camp sites. The Spanish were perplexed by the place and so were the English. It was a problem of entry, perception, discovery, mapping, claiming territory and finding familiar points of reference. Journalists and poets didn’t know how to write about it. Artists didn’t know how to paint it. There was no real center, no overarching theme or landmark, no mountain, canyon or picturesque waterfall. The Glades splayed and sprawled and seeped restlessly southwards from Lake Okeechobee in the river of grass that conservationist Marjory Stoneman Douglas wrote about. But the river metaphor was misleading to many because one imagined a river as a meandering channel between two banks while this was more like a hundred-mile swathe of water without sides, only a few inches deep, continually moving southwards in a steady flow, what modern hydrographers call sheetflow or what the Seminoles called Pa-Hay-Okee, meaning grassy water.

Explorers, missionaries, surveyors, botanists and plume hunters used less dignified adjectives like dismal, barren, hideous, desolate, monotonous, lonely, lost, impenetrable, impossible, inundated, unnavigable to describe the “God-abandoned hellscape” that was the Everglades. “No obstruction offered itself to the eye as it wandered o’er the interminable, dreary waste of waters, except the tops of tall rank grass, about five feet or upwards in height, and which harmonized well with the desolate aspect of the surrounding regions, exhibiting a picture of universal desolation,” wrote army surgeon Jacob Motte who passed through during the Seminole Wars of 1836-1838. [*Journey into Wilderness: An Army Surgeons’s Account of Life in Camp and Field During the Creek and Seminole Wars, 1836-1838, via Michael Grunwald’s meticulously researched The Swamp, Simon & Schuster, 2006, p. 42.]

Today there are numerous points of penetration, gateways of a sort to the placeless place: one to the west in Chokoloskee, another to the south in a ghost town called Flamingo. A raised wooden walkway leads through a flooded cypress landscape near Monroe Station or you can paddle your kayak through the mangrove tunnels of Nine-Mile Pond. There’s also a limited access through Lake Chekika and Grossman’s Hammock although they’re often flooded during the wet season.

Today there are numerous points of penetration, gateways of a sort to the placeless place: one to the west in Chokoloskee, another to the south in a ghost town called Flamingo. A raised wooden walkway leads through a flooded cypress landscape near Monroe Station or you can paddle your kayak through the mangrove tunnels of Nine-Mile Pond. There’s also a limited access through Lake Chekika and Grossman’s Hammock although they’re often flooded during the wet season.

Of course, the real obstacle is psychological, not physical. It’s a matter of adjusting one’s expectations and learning to paint oneself into the picture, so to speak, slowing down, catching the translucent layers and hidden hues. My son and I set out on Thursday morning with bug spray, sun block, and a copy of Peter Matthiesen’s Shadow Country as our guide, a novel infested with outlaws, drifters, ragged desperados, and the man at the center, Edgar J. Watson, also known as “Bloody Watson,” who’s more complex than Hamlet. What may have once felt like a mental barrier, an impossible transition from Bling City to Pa-Hay-Okee, now proves to be quite effortless.

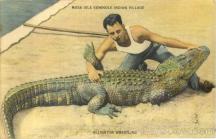

You simply retrieve the rented car from valet parking and drive west along SW 8th Street until it turns into Route 41, continue in a straight line past Krome Avenue and the pastel-pink-and-blue blob of the Miccosukee Gambling Casino, last vestige of civilization before the horizontal sweep of the Everglades unfolds with only an occasional airboat ride and alligator wrestling joint, passing over weirs, sluices and drainage canals designed to control the uncontrollable. It’s flat and repetitive, reminiscent of the polders of Holland with the same translucent, water-saturated light that Jacob van Ruisdael painted. The sky seems vast, overbearing.

You continue west on the Tamiami Trail through Water Conservation Area #3B where the natural flow of the Glades has been interrupted by canals, levees and roadways so that water has to be transferred from the north to south by a complex system of pumps and sluice gates, a kind of artificial life-support system devised by the Army Corps of Engineers.

About thirty-five miles west of the Miccosukee Gambling Casino there’s a turn off for the Shark River Slough. You can walk or take a trolley out to the observation tower, and it’s really quite a beautiful, if absurd, monument standing out there in the middle of Motte’s universal desolation, a kind of deconstructed Guggenheim Museum built during the spacy 1960s (originally a fire lookout) with a ramp and two-tiered tower rising sixty feet above the marshy expanse. Here, in this place where there’s no there, as Gertrude Stein put it, the tower provides a kind of metaphysical thereness, a 360-degree frame of reference.

About thirty-five miles west of the Miccosukee Gambling Casino there’s a turn off for the Shark River Slough. You can walk or take a trolley out to the observation tower, and it’s really quite a beautiful, if absurd, monument standing out there in the middle of Motte’s universal desolation, a kind of deconstructed Guggenheim Museum built during the spacy 1960s (originally a fire lookout) with a ramp and two-tiered tower rising sixty feet above the marshy expanse. Here, in this place where there’s no there, as Gertrude Stein put it, the tower provides a kind of metaphysical thereness, a 360-degree frame of reference.

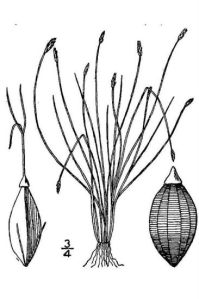

From afar, it has the presence of De Chirico’s Great Tower of 1913: lonely, spectral, melancholic, but as you get closer you can see that it splays out with a concrete pedestrian chute that makes a wide, cantilevered spiral over a boggy sump of sedges and spikerushes: needle spikerush, scallion grass, dwarf hairgrass, fewflower, false junco, umbrella hairgrass…

And then there’s the humble but mysterious Periphyton, tubular, spongy algae that clusters in mats just below the surface of the water. It provides nutrients while filtering pollutants, retains water and helps to sustain the balance of moisture in the Everglades during the dry season.

It starts to rain again as soon as we reach the top of the tower and try to take in the panorama of flooded desert, sawgrass prairie with occasional pools, narrow canals, clumps of hardwood rising slightly higher but otherwise flat and featureless to the horizon in every direction. As a destination it remains unaccommodating, resists interpretation. On first glance it looks like nothing. Maybe it takes a day or more to get used to the ineffable scale and emptiness. Maybe then you finally catch the subtle gradations of sky and light across the broader expanses. In any case, it’s a long, slow read: muted strokes of pale ochre, viridian, with slightly denser patches of tea-green, pale sea green, asparagus green, dotted here and there by tiny flecks of berry, red, umber and yellow, and unusual plants that grow in moving water like bladderwort, spatterdock, maidencane, white water lily, and a few undernourished slash pines in the distance.

A group of geriatric Danes arrive by trolley and move up the ramp as if a single Viking organism. They take photographs and hurry back down. We stay a bit longer, gazing at the sub-wash of pink-tinged heliotrope that might be a result of watery light refracted through the shallows, somehow, I’m not sure, but maybe the matte grayness of the lowering sky acts as a sponge, a kind of optical Periphyton, pulling invasive hues up from the groundscape.

On my way back from the tower, a chatty Park Ranger offers me some type of edible brown berry. Will I hallucinate? He laughs. The Calusas used it in ceremonies. It has the bittersweet tang of Scottish marmalade and leaves my mouth oddly dry with a zincish aftertaste. I jot down the name of the plant but lose the slip of paper.

We drive further west past Monroe Station and Ochopee, past America’s smallest post office, built circa 1916 for work crews on the Tamiami Trail , then left onto Route 29 and Everglades City, not a city at all but cheap motels and trailer parks with a current population of under 500. City founders like Barron Collier and the Storter family had high hopes, envisioning a marshy utopia laid out in a grid of streets and avenues–Storter, Copeland, Kumquat, Collier–with a traffic circle at the center and an imposing city hall, a bank, laundry, churches and a proper schoolhouse. They even built a trolley line through the middle of town anticipating the coming boom but no one came and most of the lots remain empty, awaiting urbanization.

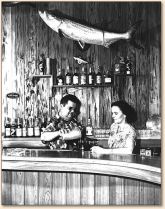

Lunch of deep-fried gator tail and frog legs at creaky Rod and Gun Club–old homestead of George W. Storter, early settler and sugar planter. The lobby glows with an orange hue from a thousand coats of shellac over walls and stuffed tarpon, alligator heads and panthers, their jaws now slack and leaking dust.

Above the reception desk hang photographs of several U.S. Presidents, earnest-eyed hunters and fishermen from the 1920s when the place flourished as a sportsman’s retreat. Hemingway came here, so did Zane Grey. Now it’s sour with ammonia and a family of possum scatter when I step through the back door, and tell myself it’s good background material for something.

But I can never claim this as narrative space for myself because it’s already been irrevocably staked and claimed by Matthiesen and his great swamp epic Shadow Country, so much so that I feel like I’m literally sliding down one of his sinewy sentences as we cross the causeway onto Chokoloskee itself: “…a baleful sky out toward the Gulf looks ragged as a ghost, unsettled, wandering.” And he’s right. The sky is ghostly, witholding rain and wandering in a way that gives me a headache just squinting at the steamy light. Maybe it’s the vapor from so many shallow estuaries, too many ions, the swamp gas or miasma that was thought to cause Malaria. I don’t have a clue. There’s a shirtless man in the shallows near the bridge, fishing with a butterfly net. A dull, blue-gray line marks the horizon as if we’d finally reached the end of the world.

But I can never claim this as narrative space for myself because it’s already been irrevocably staked and claimed by Matthiesen and his great swamp epic Shadow Country, so much so that I feel like I’m literally sliding down one of his sinewy sentences as we cross the causeway onto Chokoloskee itself: “…a baleful sky out toward the Gulf looks ragged as a ghost, unsettled, wandering.” And he’s right. The sky is ghostly, witholding rain and wandering in a way that gives me a headache just squinting at the steamy light. Maybe it’s the vapor from so many shallow estuaries, too many ions, the swamp gas or miasma that was thought to cause Malaria. I don’t have a clue. There’s a shirtless man in the shallows near the bridge, fishing with a butterfly net. A dull, blue-gray line marks the horizon as if we’d finally reached the end of the world.

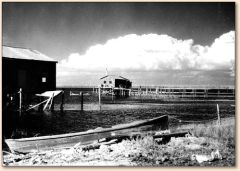

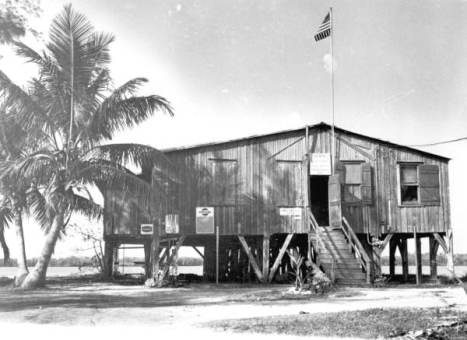

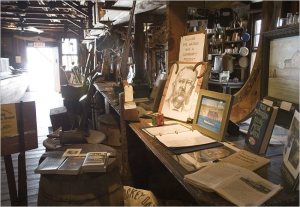

Nothing much to Chokoloskee itself, more cheap bungalows, trailer parks, shabby pre-fabs propped on concrete pylons. We turn past the Havana Café onto Mamie Street and find the pitted track that leads to Smallwood’s General Store, a wood-framed building, painted red and raised high on cedar posts to escape flood. Inside, there’s one long and poorly illuminated chamber with hardly any windows but an open door at the far end, filtering swamp-brewed light from the Gulf of Mexico. The barge-like structure was built in 1906 by Charles Sherod “Ted” Smallwood with low-pitched roof, vertical boards of termite-resistant slash pine, all of it propped high on locust posts like Noah’s Ark, ready to float away in the final Deluge. I have a sudden urge to buy something, but there’s nothing for sale other than a few old postcards.

It housed the original post office and Indian trading post and is now open as a museum of sorts, frozen in time somewhere about 1941, the year that Smallwood retired as postmaster, and a decade before the causeway to the mainland was finished. Shelves are stacked along side walls, original counters and glass vitrines in tact and stuffed with dusty relics. It also provides the opening scenography for Shadow Country: the hurricane of 1910 has just passed and the novel begins with a kind of Biblical inventory-taking of objects ravaged and rendered useless by the storm: “Pots, kettles, crockery, a butter churn, tin tubs, buckets, blackened vegetables, salt-slimed boots, soaked horsehair mattresses, a ravished doll are strewn across bare salt-killed ground...” The grounds around Smallwood’s store are still puddled with a putrefying stench of death and rank corruption. “Vultures on black-fingered wings tilt back and forth over the broken trees… stove-in boats, uprooted shacks… odd pieces torn away from their old places hanging askew, strained from the flood by mangrove limbs twisted down into the tide.”

There’s a similar tidal wash of inventory inside Smallwood’s store today: pickle jars, animal skins, moldy books and magazines, tobacco tins, old-fashioned tinctures and ointments in their original boxes, hurricane lanterns, axe handles, 1923 typewriter, sacks of raw sugar (Pearl White, Fine Granulated,) Miccosukee weavings, turtle shell, dried sponge, sawfish rostrum, gator jaws, photo albums, candy jars, coffee grinder, old pop bottles, egret plumes, ancient cash register, faded signs and photographs of how the place once looked–much the same as now–and a scale model that someone made from toothpicks and popsicle sticks. In fact, there are two scale models, one being quite elaborate and lit from within, something like the miniature spirit shrines you see along the roadsides of Southeast Asia, but in this case honoring the myth of self-sufficiency and the lost ways of frontier living.

The postmaster’s window is still there and so is Ted Smallwood’s bedroom in a back corner, gloomy with creaky bedsprings and threadbare quilt, Victorian undergarments hanging from a line over his bed. There’s also a life-sized mannequin of Ted Smallwood himself sitting in a rocking chair with a milky, infinite look in his eyes, staring out towards the bay.

On the other side of the store, someone has put together a little display, almost an altar, dedicated to the Watson legacy with letters, photographs and drawings, a charcoal rendering of the man, an oil painting of his house at Chatham Bend, newspaper clippings, letters, old pamphlets and books that tell the story. There’s even a box of shells and a shotgun that was supposedly used in his execution, and a hand-drawn sign that proudly states: “KILLING MR. WATSON WAS A COMMUNITY PROJECT.”

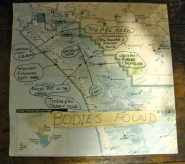

The crudely marked map has circles and arrows that point to locations where Watson’s victims were said to be buried: Lostman’s Key, Storter Bay, Opossum Key, Deer Island and if you have a morbid curiosity you can paddle your kayak down the Wilderness Waterway and visit these sites or go to the Watson place on Chatham River, twenty miles south of Chockoloskee. How many bodies did he bury in the inlets and shoals around his homestead? How many did he really kill? There’s a sign and a little dock that the park service maintains. The house burned down a long time ago but the foundation still exists as well as a cistern and some spooky remains of the Watson sugar works.

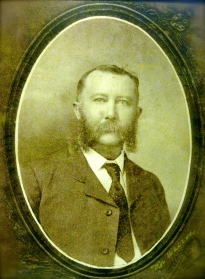

There’s a photograph of Watson himself set in a Victorian frame with a floral pattern embossed around the olive-gray matting. He’s sitting upright, wearing a tightly fitted jacket, high lapels and short tie, but I find it hard to look at the face. A surprising face, not what I’d imagined, wide and urgent, clear brow, receding hairline; high, square forehead. Wary of ambush, Watson was said to never turn his back on anyone, even a child, and there’s a cant to the head, slightly to the left, as if the photographer caught him off guard, in motion, ready for a turn, retreat or drawing of his pistol.

“He was a Scotsman with red hair and fair skin and mild blue eyes,” wrote Marjorie Douglas in the 1940s, after interviewing people who were old enough to remember the man. “He was quiet spoken and pleasant to people. But people noticed one thing. When he stopped to talk on a Fort Myers street, he never turned his back to anyone.” Was he glaring at the nervous photographer? There’s a resemblance, not unlike a certain paternal grandfather, but it’s hard to look at the old tintype and not see a serial killer. Without such foreknowledge he might be mistaken for a mid-level banker, fish-oil salesman or prominent planter, which is what he was, but there’s something in the eyes that blows that illusion. The eyes are high and creepily close together, intense and penetrating, verging toward madness.

A 19th-century phrenologist would read Watson’s high, broad forehead as obdurate, stubborn, willful and prone to outbursts of violence. The pronounced ears were said to signify lude passions according to Owen Squire Fowler, phrenologist and octagon-house pioneer, but the mouth and jaw are impossible to read because Watson sported such a thick moustache and mutton-chop sideburns as if to conceal his true, ornery nature. Were his lips full and fleshy or were they thin and coldly pursed? Did they smirk with an ironic foreshadowing of his own demise or were they locked in a permanent frown? It’s hard to tell.

A 19th-century phrenologist would read Watson’s high, broad forehead as obdurate, stubborn, willful and prone to outbursts of violence. The pronounced ears were said to signify lude passions according to Owen Squire Fowler, phrenologist and octagon-house pioneer, but the mouth and jaw are impossible to read because Watson sported such a thick moustache and mutton-chop sideburns as if to conceal his true, ornery nature. Were his lips full and fleshy or were they thin and coldly pursed? Did they smirk with an ironic foreshadowing of his own demise or were they locked in a permanent frown? It’s hard to tell.

The waxy, end-blown light inside Smallwood’s makes me feel like I’m standing inside an overexposed sepia tintype myself. My stomach is rumbling. The fried gator from lunch is crawling back up my gullet in a bid for reptilian revenge. I’m relieved to walk onto the back porch that hangs over Chokoloskee Bay and look down to the very spot where Watson pushed his boat ashore onto a bed of broken shells, just before he met his violent end that day, October 24, 1910.

We climb down a rickety staircase and stand on the murder spot. The sun is setting over the Gulf and I peer into the subfusc crawl space (more like walk space) where Smallwood kept his chickens. They were all drowned in the hurricane and the postmaster was cleaning out the sorry mess when the shootout started. “Wincing, Smallwood arches his back, takes a dreadful breath, gags, hawks, expels the sweet taste of chicken rot in his mouth and nostrils.” No chickens now, only sand and the smell of salted pine down there along with a Miccosukee dugout, beautifully carved and propped on a wooden stand. This was where the neighborhood posse gathered in twilight and gunned down E.J. Watson in cold blood.

“He never crumpled but fell slow as a felled tree… You never seen a man so dead in all your life.” More than thirty-three bullets were pulled from the bloated corpse and plunked into a coffee can. After that they stopped counting.