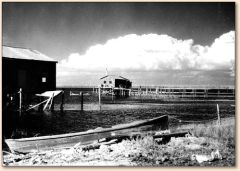

I set out on my auspicious little outing to Sanibel Island, driving across the lower instep of Florida, marshy light deflecting off the windshield, sheet-flow expanding incrementally as the car moves westward along the pencil-straight line of Route 75, otherwise known as ‘Alligator Alley’ (although I never spot a single gator along the way), past fences and swales and empty parking lots, the sky turning milky and oddly rippled with altocumulus clouds, sucking up moisture from the shallows of the Everglades.

I’m going to visit the Walker Guest House, Paul Rudolph’s little beach-house gem, built in 1952, just after Gordon Bunshaft’s Lever House opened in New York City and the nightmarish “Tumbler-Snapper” nuclear device was detonated in the Nevada desert. Richard Nixon gave his infamous Checkers speech that same month and the USS Nautilus, America’s first nuclear submarine, was launched in Groton, Connecticut. Indeed it was the heyday of the Nuclear Age, the age of the “Good Bomb” and MAD (“Mutually Assured Destruction”) with the perceived threat of Communist infiltration and back-yard bomb shelters. Into this Faustian landscape, Rudolph’s little pod dropped as an antidote to Cold-War paranoia, open to views on all sides and liberating to the human soul.

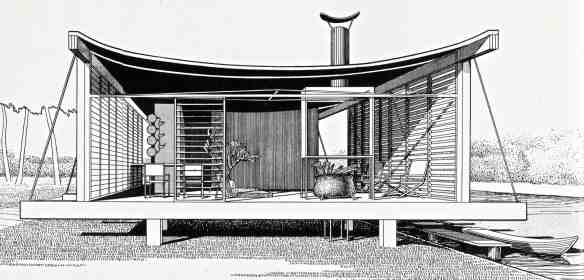

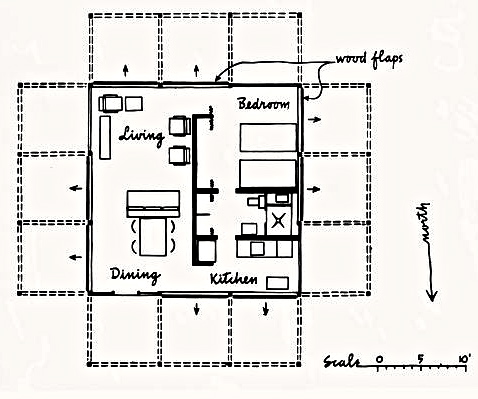

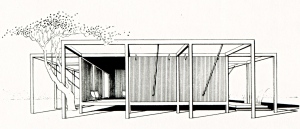

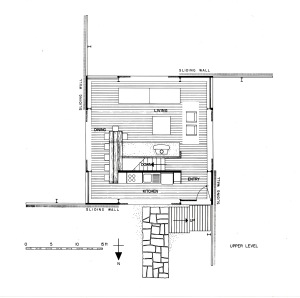

The 24-by-24-foot frame of the original rests wistfully on a bed of crushed oyster shells, high enough to catch breezes off the Gulf of Mexico and also withstand hurricane floods. An outrigger structure provides support for the ingenious, Rube Goldberg contraptions that Rudolph devised for raising and lowering the large wooden window flaps. These are hinged along the top and operated with rope and pulleys. There are eight flaps in all, two on every side, and they can be set in a variety of positions.

The most memorable elements of Rudolph’s design, however, are the eight counterweight balls (weighing 77 pounds each) that hang from steel cables and help to raise and lower the wooden flaps. This accounts for the nickname: “cannonball house” favored by family and locals, while others prefer the more prosaic “house with balls.” The spherical counterweights are said to have been cast in beach sand by pouring wet concrete into the negative form of a beach ball, a most poetic touch, but one that may be apocryphal.

The most memorable elements of Rudolph’s design, however, are the eight counterweight balls (weighing 77 pounds each) that hang from steel cables and help to raise and lower the wooden flaps. This accounts for the nickname: “cannonball house” favored by family and locals, while others prefer the more prosaic “house with balls.” The spherical counterweights are said to have been cast in beach sand by pouring wet concrete into the negative form of a beach ball, a most poetic touch, but one that may be apocryphal.

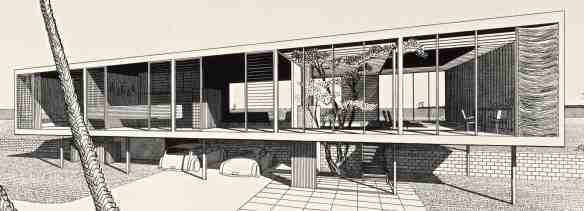

Rudolph’s single-family vacation homes of this period were thoroughly urban constructs with flat roofs and floor-to-ceiling glass. (The Miller Guest House in Casey Key, built in 1949, and the Cocoon House on Siesta Key, built in 1950, were the earliest examples.) They signaled independence, self-sufficiency, and a celebration of the natural elements: sun, sea and a well-shaken martini. While providing little more than shade and a place to sleep, the Walker house expressed an open-ended lifestyle for a generation who’d survived World War II and were intent on building a brighter, more hopeful future for themselves and their families. Today, the house can be seen as a prototype for sustainable living with its small footprint and simplicity of plan. It was inexpensive, self-cooling, raised against floodwaters, and easily closed up for hurricanes. Just as importantly, it was light-hearted, even whimsical, with its dangling cannonballs and flip-top walls, fitting seamlessly into the natural setting, and barely disrupting the sandy contours of the Sanibel beachfront.

The Walker house was the first independent commission after Rudolph established his own firm., and Walter Walker proved to be an ideal client: son of a prominent Minneapolis family, culturally sophisticated and with a love for the outdoors. He was the grandson of T.B. Walker, the Minnesota lumber baron who’d given his renowned art collection and part of his fortune to create the Walker Art Center. He went to Harvard medical school but ended up working in the family lumber business. In his 30s, he contracted tuberculosis; the family physician prescribed a warm, quiet place to recover. This was originally why Walter bought the waterfront lot on Sanibel Island as a kind of one-man sanatorium, but he didn’t think about building a house there for another few years. In 1950, he contacted Sarasota-based architect Ralph Twitchell, who advised him to hire his young associate, Paul Rudolph. “He’s fresh out of Yale and full of ideas,” said Twitchell. Walker took his advice and commissioned Rudolph to design a small guesthouse on a back corner of the property. (Later, in the 1970s, a much bigger house would be built on the dune overlooking the Gulf.)

Rudolph worked with basic materials that could be found at any lumberyard. Standard lengths of two-by-four lumber were doubled up to create I-beam-style supports for the footings, and the hurricane flaps were made from plywood and peg-board sandwiched together. It was to be the simplest of pavilions. Its many openings were originally designed without screens, but Walker insisted on having them to keep out mosquitoes and sand flies. He spent the next 30 winters living there until finally building a larger house on the top of the dune.

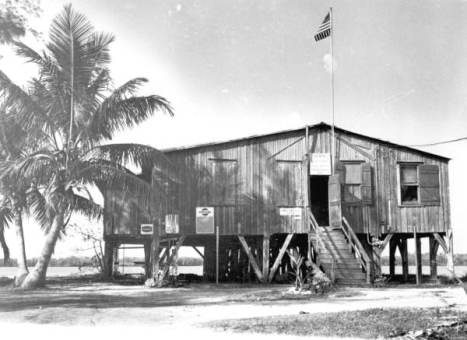

Up at the main house, the sun is bright, almost blinding, and Mrs. Elaine Walker, a spry 91 years old, sits on a shaded porch, looking out at the liquid light rising off the Gulf of Mexico. She is warm and welcoming with a mischievous glint in her eyes. “There was  nothing here. It was the absolute boonies!” she says, laughing. “There wasn’t even a telephone!” Wearing a blue-green dress and bone-white spectacles, she sits in a low-slung hammock chair and explains how she met her husband Walter in the 1960s. He’d recovered from tuberculosis by then but was going through a drawn-out divorce, as was she. “We kept going out to dinner and then we fell in love,” says Elaine. After dating for almost two years, they decided to get married, but when Walter brought her to his little escape pad on Sanibel Island, she was shocked. “He told me that he had this little house in Florida and when I came down from Minneapolis I thought ‘Why would anyone want to build in such a place?’ It was so isolated and I’m a city kid by nature.” The roof leaked when it rained and there were gopher tortoises living in the crawl space. When Elaine wanted to make a phone callshe had to walk half a mile up the dusty shell road. “You call this a house?” she said. “Not exactly what I’m accustomed to–only 24 by 24 feet–you must be kidding!” But Walt loved it small and simple, and he liked to lie in a hammock strung between two palm trees and watch pelicans skim across the water, counting them as they passed. By the end of the first winter season, Elaine was learning to adapt to the quirkiness of Rudolph’s little experiment. “It was just like camping and I learned to be a good girl scout,” she says. “I’d always wanted to be a Girl Scout.” She and her husband would go swimming in the morning, collect shells along the beach and read books. Elaine pinned up a few art posters and Walt made little scenes out of driftwood and shell. He even agreed to put in a telephone. “It was really quite charming, after all,” she admitted.

nothing here. It was the absolute boonies!” she says, laughing. “There wasn’t even a telephone!” Wearing a blue-green dress and bone-white spectacles, she sits in a low-slung hammock chair and explains how she met her husband Walter in the 1960s. He’d recovered from tuberculosis by then but was going through a drawn-out divorce, as was she. “We kept going out to dinner and then we fell in love,” says Elaine. After dating for almost two years, they decided to get married, but when Walter brought her to his little escape pad on Sanibel Island, she was shocked. “He told me that he had this little house in Florida and when I came down from Minneapolis I thought ‘Why would anyone want to build in such a place?’ It was so isolated and I’m a city kid by nature.” The roof leaked when it rained and there were gopher tortoises living in the crawl space. When Elaine wanted to make a phone callshe had to walk half a mile up the dusty shell road. “You call this a house?” she said. “Not exactly what I’m accustomed to–only 24 by 24 feet–you must be kidding!” But Walt loved it small and simple, and he liked to lie in a hammock strung between two palm trees and watch pelicans skim across the water, counting them as they passed. By the end of the first winter season, Elaine was learning to adapt to the quirkiness of Rudolph’s little experiment. “It was just like camping and I learned to be a good girl scout,” she says. “I’d always wanted to be a Girl Scout.” She and her husband would go swimming in the morning, collect shells along the beach and read books. Elaine pinned up a few art posters and Walt made little scenes out of driftwood and shell. He even agreed to put in a telephone. “It was really quite charming, after all,” she admitted.

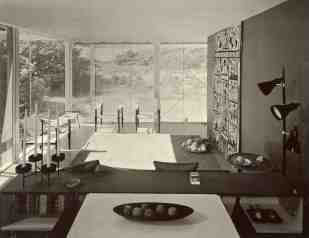

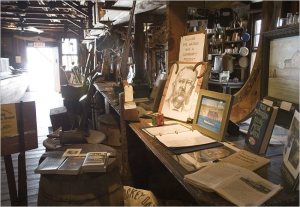

Even with only 580 square feet of internal living space, the house felt expansive with its all-around views and basic geometry. The interior was divided into equal quadrants for dining, cooking, living and sleeping, something like a well-ordered boat, with everything in its place. Rudolph had worked as a naval architect during World War II. He learned about thin-shell construction and how to make the most efficient use of space. “I was profoundly affected by ships,” he wrote. “I remember thinking that a destroyer was one of the most beautiful things in the world.” Rudolph would apply what he’d learned in the shipyards to the Walker Guest House and other projects. In early photographs you can see that he’d originally used a deep indigo blue in the living/dining area to create a cool, cave-like space and offset the sun-struck dunes that surround the house. He designed most of the furniture himself, including a steel-and-glass dining table, a low-lying bookcase as spatial divider in the living room, and several deck chairs. Floors were charcoal gray linoleum and the ceiling was covered in a pale grass-cloth to create texture. “It was just as cozy as could be,” said Elaine Walker, remembering the times she stayed in the house during inclement weather. The flaps could be lowered half way to keep the rain out but there was still enough light for indoor activities. “You know, Rudolph told my husband that sometimes it’s nice to be in a cave and sometimes it’s nice to be in a pavilion,” she said. “With the flaps down it was a cave. With the flaps up it was a pavilion.” With a few adjustments the flaps could also be made to funnel Gulf breezes through the house, as there was no air conditioning, but occasionally it was sweltering and Mrs. Walker remembers having to run down to the beach every half hour for another dip in the Gulf. “I never got out of my bathing suit,” she said.

The skeletal structure fulfilled Rudolph’s desire to make the house “crouch like a spider in the sand,” with spindly legs reaching out on all sides, eroding all sense of mass. The house’s profile would change almost daily, depending on the weather, the season, the angle of light and the moods of the homeowners. The counterweights moved up and down so that when the flaps were shut, the balls hung high and when the flaps were open, the balls hung low. The wood bracing, pull ropes and tension cables also created narrow lines of shadow–a kind of drawing or delineation–that Rudolph used to further animate his three-dimensional composition.

When construction was finished, Walter Walker climbed up on the roof and detected a slight lateral movement in the bones of the structure. He called Rudolph and the architect quickly devised a solution: crisscrossing tension cables were strung across the openings to strengthen the structural integrity of the framework.

McCall’s Magazine

The guesthouse received an inordinate amount of attention for such a modest commission. McCall’s Magazine ran a feature in 1956 with color photos and a breezy text about the “house for carefree summer living.” (Plans could be purchased from the magazine for 25 cents.) It appeared in architecture journals and became an inspiration to a generation of young American architects. Peter Blake, architect and friend of Rudolph, designed his own house in Water Mill, New York, in the same configuration with a 24-foot-by-24-foot floor plan. Instead of hinged wooden flaps, however, Blake used horizontally sliding barn doors that could be moved back and forth on metal tracks, but it was essentially the same idea: a box that could be shut up for a hurricane or a season.

“I had no idea that our little guesthouse would become so famous,” says Mrs. Walker. “It’s really quite revered in the world of architecture so we try to maintain it as best as we can.” The counterweight balls were originally painted a bright pimento red, like an exotic fruit, and stood out in contrast to the white walls of the house. Now, they’re more of an aubergine or purplish red, while the woodwork has been painted a pale gray in place of the original white. “I like a little bit of change now and then,” says Mrs. Walker who has kept the house in pristine condition ever since her husband’s death in 2001. Windows are re-sealed; wood surfaces are sanded and painted fresh almost every year, while an assistant keeps the mold at bay with frequent doses of bleach.

Apart from a few minor repairs, the house is made of the same materials it was built with in 1952. Even the fixtures in the tiny kitchen and bathroom are original. After years of exposure, the wooden flaps have become water logged and harder to lift. It usually takes two people to open them. “My husband would stand inside and pull the rope while I would go outside and push with my fanny,” explained Mrs. Walker.

Jack Priest, her son-in-law, stands in the doorway of the little guesthouse, wearing pink rubber clogs and a marlin-print shirt. He points to a metal escutcheon in the ceiling and explains how one of the pull ropes breaks every so often and has to be replaced and threaded through a hidden pulley, out through a hole in the fascia board. “It takes real concentration,” says Priest, who’s learned how to guide the rope through the openings with a stiff wire.

Jack Priest, her son-in-law, stands in the doorway of the little guesthouse, wearing pink rubber clogs and a marlin-print shirt. He points to a metal escutcheon in the ceiling and explains how one of the pull ropes breaks every so often and has to be replaced and threaded through a hidden pulley, out through a hole in the fascia board. “It takes real concentration,” says Priest, who’s learned how to guide the rope through the openings with a stiff wire.

Elaine Walker and her family — her children and grandchildren — continue to cherish the diminutive scale and close-packed ingenuity of a house that forces everyone to slow down and return to the simple pleasures of waterfront living — picnics, swimming, outdoor showers, beach combing, living in synch with nature — so that winter vacations on Sanibel have become a beloved family tradition. “I didn’t come to appreciate the architecture for a long time,” admits Mrs. Walker. “But it was wonderful to be in a place that made my family so happy.”

Paul Rudolph’s name has been tossed about in the news lately because several of his buildings are under threat of demolition. While the early beach houses are generally cherished and well monitored, the concrete walls and bulky forms of his later “brutalist” buildings are harder to love. Many find them cold and alienating, such as the Orange County Government Center in Goshen, NY (1967) that is scheduled to be torn down in the next few months. As a kind of precautionary measure, the Sarasota Architectural Foundation (SAF) recently announced that they are creating a full-scale replica of the Walker Guest House, one of Rudolph’s crowning achievements. Architect and contractor Joseph King is fabricating the facsimile in his workshop in Bradenton, just north of Sarasota. Sponsored by the SAF and Dr. Michael Kalman, the revision will be exact in every detail except for the fact that this 21st-century variation will be a demountable kit of parts, easily broken down and moved from venue to venue. King is milling all sections from micro-laminate lumber that will help to strengthen the structure. Parts will be attached with screws and bolts instead of nails, but as per the original, linoleum will cover the floors. (The Armstrong Flooring company happens to still make the same charcoal gray product.) When finished, it will be a walk-though artifact for the purpose of educating people about mid-century modernism and the architectural legacy of Paul Rudolph. Even the furniture that Rudolph designed for the interior is being replicated. The facsimile edition of the Walker Guest House will be unveiled in November 2015 and remain on the grounds of the Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota for another 11 months. After that, it is scheduled to travel to Miami in time for Art Basel Miami 2016. For info: http://www.ringling.org/

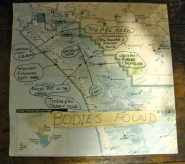

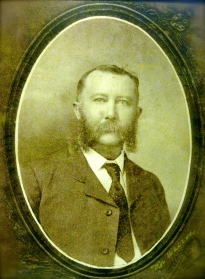

A 19th-century phrenologist would read Watson’s high, broad forehead as obdurate, stubborn, willful and prone to outbursts of violence. The pronounced ears were said to signify lude passions according to Owen Squire Fowler, phrenologist and octagon-house pioneer, but the mouth and jaw are impossible to read because Watson sported such a thick moustache and mutton-chop sideburns as if to conceal his true, ornery nature. Were his lips full and fleshy or were they thin and coldly pursed? Did they smirk with an ironic foreshadowing of his own demise or were they locked in a permanent frown? It’s hard to tell.

A 19th-century phrenologist would read Watson’s high, broad forehead as obdurate, stubborn, willful and prone to outbursts of violence. The pronounced ears were said to signify lude passions according to Owen Squire Fowler, phrenologist and octagon-house pioneer, but the mouth and jaw are impossible to read because Watson sported such a thick moustache and mutton-chop sideburns as if to conceal his true, ornery nature. Were his lips full and fleshy or were they thin and coldly pursed? Did they smirk with an ironic foreshadowing of his own demise or were they locked in a permanent frown? It’s hard to tell.