An early settler described the waters off of Coconut Grove as being “afloat on a sort of liquid light, rather than water, so limpid and brilliant is it”. Another described a “veritable fairyland of wonders, beauties and unpolluted purity”. Over its 100-year history, Coconut Grove has grown into a unique entanglement of culture and nature.

It is the oldest continuously inhabited community in Miami. Where other parts of the city are about standing out–being conspicuous in one’s show of wealth and status–the residents of the Grove pride themselves on a certain restraint, preferring to lay low beneath the lush canopy of trees. The legendary canopy shades most of the village with a dense weave of leaves, limbs and vines of the gumbo-limbo, swamp laurel oak, banyan, mahogany, coconut palm, fig, mango, bullet tree, making up the only true jungle in North America. Longtime residents are particularly proud of the natural legacy and talk about the canopy as if it were a singular living entity with a soul of its own. Marjory Stoneman Douglas, outspoken journalist, feminist, naturalist who lived in the Grove for 83 years, wrote poems about the canopy and the “dark lift of trees [where each leaf] pools its separate and particular moon gleam”.

Since its inception in the 19th century, the Grove has been known for its fiercely independent spirit, going back to the early settlers, the wreckers and tolerant, free-thinking writers, naturalists, suffragettes and artists, growing into a diverse melting pot of cultures that includes a black Bahamian community (West Grove) and one of the first fully integrated school systems in Dade County. When the City of Miami forced an annexation referendum in 1925, the majority of Grove residents voted to remain an independent municipality, but they were outnumbered. Subsequent generations have continued to rebel and fight for political autonomy, attempting to de-annex the village from greater Miami.

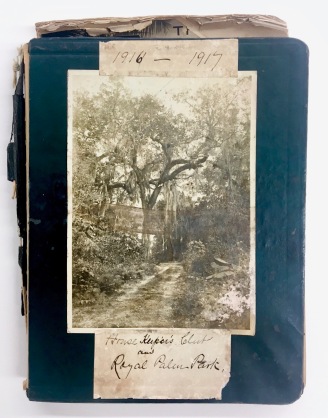

“The people who settled Coconut Grove have cultivated their gardens to such good effect, that they have planted trees and set out vines on old walls, and kept intact, successfully, the tangles and by-paths [of the past]”, wrote Douglas. Vintage black-and-white photos from the mid-19th century show plaited fronds and the riotous tangle that she described: thatch, serpentine roots, dangling air shoots of the banyan, palmetto scrub, spiky agave, mangrove “walking trees”, as if the air itself were sprouting new life.

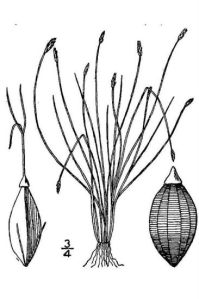

By the post-Civil War era a few souls begin to appear among the shadowy grain, as if hidden among the thickets: pioneers, lighthouse keepers, wreckers, plume hunters, Bahamian sponge fishermen, subsistence farmers. There are men, like the two Pent brothers, clearing ground with machetes, building homesteads, harvesting coontie, the small, palm-like Zamia that grows wild in the pine woods around the Grove. They grate and grind the roots by hand to make a kind of starch, similar to arrowroot, that is much in demand and brings good money.

Land was divided up into 160-acre blocks in accordance with the Homestead Act of 1862. A homesteader can claim a plot, pay a small filing fee and then live on the site for five years before receiving title from the government. Early homesteaders include Dan Clarke, an old man who lives in a cabin by the bay. Johnny Frow builds a house out of fine white pine, most of which he “borrows” from the wreck of the Three Sisters, after the hurricane of 1876. Judge T.W. Faulkner has a place at Snapper Creek, while Sam Rhoads, a prospector, lives with his son, Walter, near Dinner Key.

Dr. Horace Philo Porter opens the first post office in 1873, calling the village “Cocoanut Grove”, even though there are only one or two coconut palms in existence at the time. Charles “Jolly Jack” Peacock arrives from London with his wife Martha Snipes and an army of children–nine sons, two daughters–and they settle in a compound at the Southwest end of the curving bay or “bight”. Indeed, the bay-front area will thereafter be known as “Jack’s Bight”. Ned Pent is a boat builder but makes extra money making coffins. He is known to drink quite heavily and one night, while making a coffin, gets confused and fabricates the coffin complete with a centerboard.

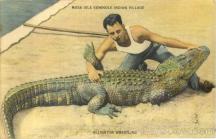

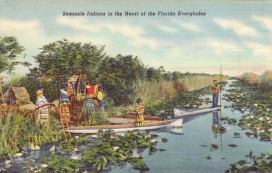

The Grove becomes a fluid, interdependent community of year-round residents, winter visitors as well as a number of Seminole Indians who paddle out of the Everglades in their dugout canoes and come to the Settlement to trade alligator skins, egret plumes, sweet potatoes and pumpkins in exchange for flour, calico fabric, buttons, knives and other dry goods. There’s Cypress Tiger and Big Tiger, son of war chief Tigertail, and other Seminoles who gain trust and are gradually accepted as part of the greater Grove community.

RUSTIC BOHEMIA: 1833

Charles Peacock and his wife Isabella, also known as the “Mother of Coconut Grove”, move from London to the Grove on the urging of Charles’ brother, “Jolly Jack”. They buy 31 acres of bay-front property–a section of John Frow’s original homestead–and build a two-story house that they name “Bay View Villa”. The couple begin to take in guests and change the name to the Peacock Inn, the first hotel in Miami-Dade, that soon becomes the Grove’s social centrifuge for the next twenty years (1883-1902). A room costs $10 a week and sailboats can be rented for $2 a day. The dining room is the only real restaurant in the area. Henry Flagler eats there during his first visit to Miami. The Peacocks’ afternoon teas are also popular and attract an eclectic mixture of winter visitors and locals.

By the mid-to-late-1880s, a different breed begins to appear: outsiders from the north escaping winter weather: gentlemen wanderers, intellectuals and literary types, ministers, sailing enthusiasts, independent women, amateur botanists, student drifters, making the Grove into a kind of rustic bohemia and South Florida’s first real destination, years before Miami became a popular retreat.

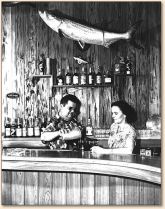

The prime tourist era begins in the winter of 1886-1887 when curious northerners descend and fill the rooms of the Peacock Inn. Christmas is celebrated at the inn with almost everyone then living in the area. Dinner is a feast that begins with grapefruit and sliced mango, followed by green turtle soup, a platter of baked land crabs, a main course of broiled mangrove snapper with grits and French-fried dasheen, and lastly a salad of palm cabbage with coconut jelly and orange flower honey.

Soon there are even more winter visitors and the original inn expands with several additions, a two-level porch and sharply pointed dormers. Several new out buildings are also built including a boathouse, changing rooms for bathers at the water’s edge, and additional guest cottages. An informal salon begins to meet on the inn’s front porch while other guests come and go. One of the regulars is Kirk Munroe, a journalist and author who writes adventure books for boys: The Belt of Seven Totems; Ready Rangers; Through Swamp and Glade.

A photograph taken by Ralph Munroe (circa January 12, 1887) shows the cast of characters, many of them will play major roles in the Grove’s future development. It’s a moment of 19th-century idyll captured for posterity, something that Gustave Caillebotte might have painted, or Renoir. Some are sitting casually, slouching on the Peacock’s front steps. Others are standing to the side, looking directly at the camera or at a slight angle. There’s the writer Kirk Munroe, and Thomas Hines, and the botanist Isaac Holden, and Rev. Charles E. Stowe (son of Harriet Beecher Stowe); Miss Flora McFarlane; and two who claim descent from European nobility: Count Jean D’Hedouville from Belgium, and Count James L. Nugent, a strikingly tall and bearded Frenchman whose grandfather was a general under Napoleon. Then there’s Mary Barr Munroe, Kirk Munroe’s pathologically shy wife, who has her back turned to the camera. It’s as if all had been posed like that by the photographer, to make the most artistic composition possible.

A photograph taken by Ralph Munroe (circa January 12, 1887) shows the cast of characters, many of them will play major roles in the Grove’s future development. It’s a moment of 19th-century idyll captured for posterity, something that Gustave Caillebotte might have painted, or Renoir. Some are sitting casually, slouching on the Peacock’s front steps. Others are standing to the side, looking directly at the camera or at a slight angle. There’s the writer Kirk Munroe, and Thomas Hines, and the botanist Isaac Holden, and Rev. Charles E. Stowe (son of Harriet Beecher Stowe); Miss Flora McFarlane; and two who claim descent from European nobility: Count Jean D’Hedouville from Belgium, and Count James L. Nugent, a strikingly tall and bearded Frenchman whose grandfather was a general under Napoleon. Then there’s Mary Barr Munroe, Kirk Munroe’s pathologically shy wife, who has her back turned to the camera. It’s as if all had been posed like that by the photographer, to make the most artistic composition possible.

A few weeks later, there’s a Washington’s Birthday regatta in the waters off of Coconut Grove. William Brickell, skippering gaff-rigged Ada, is the winner. After the race, a group of yachtsmen enjoy a celebratory dinner at the Peacock, and this leads to the formation of the Biscayne Bay Yacht Club. Ralph Munroe serves as commodore, Kirk Munroe is secretary and his wife, Mary, designs the yacht club pennant that is raised over Munroe’s boathouse.

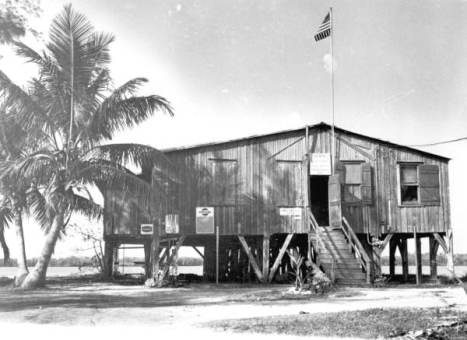

Using lumber salvaged from a wrecked ship, a small Sunday-school building is built in 1887, not far from the inn, with pitched roof and vertical board-and-batten siding. The one-room structure serves as a makeshift church until a proper stone edifice is built in 1916.

FIGURES IN A LANDSCAPE: 1891

Ralph Middleton Munroe is a man of many talents: sailor, marine architect, naturalist, photographer, author, and accomplished builder. After spending several winters at the Peacock Inn, he decides to build his own home on a property just south of the inn. First, he constructs a boathouse and lives on the second floor while completing work on the main house, a one-story structure raised up on columns, eight feet off the ground. The front porch is decorated with crisscrossing ornamental brackets that have a rustic, oriental feel, a theme that is emphasized by the tapering pagoda-type roof clad in terracotta tiles.

There’s a Chinese-lantern lightness reminiscent of Andrew Jackson Downing’s stick-style houses in the Hudson valley, and Munroe’s self-built home is unabashedly romantic, playful, exotic and sets the tone for many other Grove houses to come. The center foyer is an octagon with rooms branching off from every side. A square cupola for ventilation sits at the very peak and helps to cool the interior. The pyramidal shape of the roof with its central opening are the reasons that Munroe decides to name his house “The Barnacle”.

Munroe poses his subjects in wildly overgrown settings. At first, it’s hard to even see the person. Human figures blend into the background of tangled roots and palm fronds, and are almost invisible. The eye adjusts to the wild patterns and then, only gradually, a face, a hand, a full body begins to emerge, not unlike the hidden figures in Henri Rousseau’s jungle tableaus.

A young girl, about ten years old, sits on a downed gumbo-limbo tree. Her hair is long and curly, matching the texture of the palm fronds and gnarled branches that surround her. One can detect a certain amount of stagecraft. Perhaps the photograph, however naturalistic it seems, is not entirely of the moment. (Munroe works out his compositions while lying in bed at night). His camera is a cumbersome, large-format instrument He has to cut away a clearing just to set up the tripod. Undergrowth is flattened to make room for the apparatus and the subject. Several palmetto fans are bent back, and the girl appears to be propped there, in the middle of the frame, smiling but a little unsure of herself, a little uneasy. On closer inspection, you can see the long stick she’s using to balance herself on the limb of the tree, a propping device that Munroe uses in other photographs.

An older woman stands among a densely woven landscape of gnarled oak branches and exposed roots. She is standing on top of a thick, curving mangrove root, as if hovering in suspension, and uses the same long stick to keep herself from falling). A 20-year-old woman is dressed in her Sunday best, a striped dress with ruffles, a straw, and she’s propped high on a felled oak tree, playing a banjo.

Dr. Eleanor Galt Simmons becomes the first woman to practice medicine in the Grove. She and her husband, Captain Albion Simmons, build a small barn on their property––the future Kampong––using native limestone. (Her brass nameplate is still on the door). This becomes her clinic where she treats winter visitors, locals and also cares for the Seminoles who come to her for medicine. Some days, she makes her rounds in a small sailboat. On the side, she and her husband start a business making and exporting jelly and wine from the fruit they grow on the property.

On April 15, 1896, Henry Flagler’s East Coast Railway reaches Fort Dallas on Biscayne Bay, the site of present-day Miami. At the time, it’s a settlement of fewer than 50 inhabitants. A few months later, the name is changed and Miami is officially incorporated as a city with a population of just over 300. The main railway station is there, but the Grove gets its own station near the intersection of Day Avenue and Douglas Road and this has a gradual effect, changing the configuration of the town by pulling development further west, away from the bay, towards the railroad line. Flagler builds the Hotel Royal Palm on the north bank of the Miami River. The grand, five-story building has 450 guest rooms and boasts the area’s first electric lights, elevators, ballroom and swimming pool.

The railway and hotel have an immediate impact on the area, bringing hundreds of new visitors: sun seekers, dreamers, land speculators. Over the next few years, Miami will grow exponentially from a tiny settlement to a population of several thousand, soon overshadowing the Grove.

The Grove has a legacy of strong, independently minded women, community leadership and a pioneering form of feminism that go back to the earliest days of the settlement. Flora MacFarlane, the first woman homesteader and the Grove’s first school teacher, founds the Housekeeper’s Club in 1891 with the purpose of educating young women and serving the community at large. The original wood-framed clubhouse is built in 1897 on land donated by Ralph Munroe. Club members put on pageants, picnics, and organize a series of gala events designed to raise money for charitable causes.

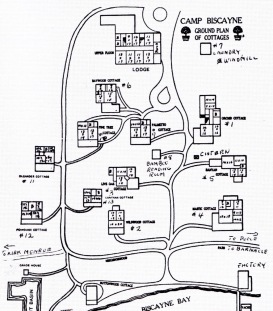

The Peacock Inn goes out of business in 1902, and the Grove loses its social/cultural center. Ralph Munroe establishes Camp Biscayne on a long narrow lot that stretches from the main road down to the edge of Biscayne Bay, only 250 feet south of where the inn stood. A Main Lodge a

The Peacock Inn goes out of business in 1902, and the Grove loses its social/cultural center. Ralph Munroe establishes Camp Biscayne on a long narrow lot that stretches from the main road down to the edge of Biscayne Bay, only 250 feet south of where the inn stood. A Main Lodge a nd 12 quaintly designed cottages are spread across the property, connected by winding pathways. Each cottage is named after one of the trees or plants that grow on the property: “Oleander Cottage”, “Banyan Cottage”, “Orchid Cottage”, etc. At the very center of the property is a little reading room made out of bamboo. Camp Biscayne is a comprehensively planned compound, the first “gated community” in South Florida.

nd 12 quaintly designed cottages are spread across the property, connected by winding pathways. Each cottage is named after one of the trees or plants that grow on the property: “Oleander Cottage”, “Banyan Cottage”, “Orchid Cottage”, etc. At the very center of the property is a little reading room made out of bamboo. Camp Biscayne is a comprehensively planned compound, the first “gated community” in South Florida.

FOUR WAY LODGE: 1915

The quietly diminutive scale of early Grove architecture begins to be challenged by the scale and relative extravagance of several new houses such as Four Way Lodge, William J. Matheson’s rambling rustic affair with rough-hewn cypress arbor for shade, and a hint of Japanese temples in the horizontal lines and the low belvedere with hip roof. Matheson is an industrialist, born in Wisconsin, educated in Scotland and founder of the National Aniline and Chemical Company. The house, built on what is now Poinciana Avenue, is named after Kipling’s poem: “Now the Four-way Lodge is opened, now the Hunting Winds are loose”, and is designed by Robert W. Gardner, a New York architect who professes to be an expert in ancient Greek vernacular.

Matheson is all style and becomes one of the most recognized personages in the settlement. Whenever he leaves his house for a walk through the Grove’s byway, he wears perfectly buffed white shoes, a five-button linen jacket and a winged bow tie, the rim of his Panama hat pushed back in a rakish manner.

Matheson is also a restless soul, always launching new projects. After only a few years, he sells Four Way Lodge and builds himself a much larger house that he names “Swastika Lodge”, after the ancient Sanskrit word for “good fortune”. (Because of its associations with the Nazis, the name will later be changed). It is built at 3645 Ingraham Highway on a 15-acre lot, with a wide breezy veranda overlooking Biscayne Bay. Dubbed the “most southerly house in the United States”, Swastika Lodge features exotic vines growing up the walls and evokes the feeling of a deluxe Robinson Crusoe hideaway. The spacious living room is filled with artifacts that Matheson gathered during his world travels: pottery from South American, teapots from Japan, lanterns from China, tribal spears from Africa.

David Fairchild buys the Kampong from Mrs. James Nugent and converts the seven-acre property into a family home and experimental laboratory where he begins to plant some of the tropical species he has brought from around the world. The seven-acre garden flourishes and eventually expands to nine acres as Fairchild claims this part of south Florida as the only true sub-tropical jungle in North America.

The Plymouth Congregational Church opens its doors at 3429 Devon Road in April, 1916. Known as the “Church in the Garden”, it’s designed by New York architect Clinton McKenzie in the Spanish Mission Style with twin bell towers, corrugated clay roof tiles and the walls are made from native oolitic limestone. (All of the stonework is done by Felix Rebom, a local mason). The exterior of the church is soon covered by thick pelts of ivy, giving it a rusticated, ancient look, even though it was built in the 20th Century. The big, oak-and-walnut front door is, however, the real thing. The 400-year-old artifact was relocated from a monastery in the Pyrenees Mountains of Spain.

MILLIONAIRES ROW: 1917

Architectural tastes shift. The casual bungalows and compounds of the early years give way to a grandiose scale and eclectic mix of Mediterranean, Italianate and neo-classical styles. The big new estates are designed for wealthy denizens who have begun to flock to the Grove: oil and railroad tycoons, steel magnates from Pittsburgh, automobile barons from Detroit. It’s no longer the easy-going flow of the early settlement. Property lines are redrawn, old trees removed, formerly open boundaries are walled off and gated.

The simple, back-to-nature charms of Camp Biscayne are replaced by a baronial mansion for A. H. Swetland. Architect George Fink conceals the house from prying eyes with high walls and ornate metal gates. Kirk Munroe sells “Scrububs”, his rustic, bay-front property, to attorney John B. Semple from Pittsburgh who hires Richard Kiehnel to design “La Brisa”, a rambling Mediterranean style mansion with loggias and shaded arcades branching off from a central tower. Pittsburgh steel magnate, John Brindely, builds El Jardin, a Renaissance palazzo on a ten-acre site overlooking Biscayne Bay. The Mediterranean-style stonework is specially aged to make it look ancient.

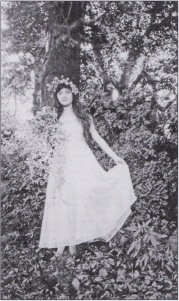

While the rest of the world is still at war, a contingent of ladies from the Housekeeper’s Club gather for an afternoon of pageantry at Bindley’s romantic El Jardin. They are dressed in diaphanous Greek costumes, flowing multi-layered gowns, headbands made from lace and silken fripperies. All is hushed as pretty little Eunice Isabella Peacock–14 years old–prances her way up the garlanded pathway like a nymph with strands of wild flowers (larkspur, swamp rose, hurricane lily), all twisted and plaited throughout her wild red hair. She pauses for a moment in front of the vestal virgins–or whatever classical legends the ladies are meant to represent–then dances her way across Brindley’s sprawling poolside terrace and out the other end of the grotto while a shirtless boy in Puck-like pantaloons stands atop the coral colonnade and plays a hauntingly simple tune on the panpipes.

During the great freeze of 1917, ice forms to a quarter inch on exposed water buckets in Coconut Grove. Thousands of swallows fall out of the air, dead, frozen in mid-flight.

“…the stones walls, carved and scalloped,

were surmounted by endless festoons of

ramblers and creepers. Within the immense

gardens stood a palace of pillared

splendor, crammed with such treasures

gathered from the Old World that the mind

grew dizzy under the fabulous story of one

man’s wealth, derived from selling ploughs

and reapers to farmers…”

– Cecil Roberts

There are hardly any signs of economic strife, no Great Depression, no sense of time or history in the golden land of unbridled entitlement. Cecil Roberts, English travel writer, has only just swanned into Florida from a dreary winter in London. He falls instantly under the intoxicating spell of the Grove’s sea-flecked light, its tropical canopy, banyans, hedges of hibiscus and bougainvillea. He makes a tour of Vizcaya and some of the other estates along Millionaire’s Row.

Roberts visits Villa Woodbine, the home of industrialist Charles Boyd, built high on a ridge overlooking Biscayne Bay. He is entranced by the formal allée of Royal Palms that lead the way into Ernest C. Coles’ “Treasure Trove”, and the manicured grounds that feature a heart-shaped pool, statues of Neptune and other mythological figures, and a collection of rare tropical plants that Coles has imported from around the world. Roberts is also invited to see “Entrada”, an entire compound of breezy Mediterranean villas that Hugh Matheson has built at the southern end of the Grove. The 20-acre property features man-made canals and a yacht basin. But none of the estates in all their glory can come close to elegance or sheer magnitude of Vizcaya, James Deering’s 180-acre wonderland at the northern end of Coconut Grove.

Even though it was supposed to be only a short visit, Roberts decides to stay for another month and he writes a dreamy account of the wealthy denizens and luxurious estates of the Grove, but his first impression is of Vizcaya and it colors everything else he sees. The Italian-Renaissance palazzo appears as if ancient, rusticated by the centuries, but it’s less then twenty years old, and Deering, its creator, has only just died at the age of 65 while sailing back from Europe aboard the SS City of Paris. The man has already assumed mythic stature, and Roberts hears many different tales––some true, some wildly exaggerated––about how the eccentric socialite and heir to the Deering Harvester fortune, hired a special train to transport the entire cast of the Ziegfeld Follies down from New York for his personal amusement; or how Deering arrived at his own house-warming party in a gondola, dressed as a Renaissance prince; or how he collected monkeys and exotic birds in specially designed cages; or how he projected Charlie Chaplin movies onto the side wall of his estate.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby is published in 1925, the same year as Deering’s death, and it’s hard not to detect certain similarities between the two. One long-time acquaintance describes Deering as “a reticent man with impeccably proper manners,” and he was an enigmatic figure who few people really got to know. He never married. He seemed anxious, troubled, uncomfortable in his own skin. He hated to be photographed, and was quite obsessed with bringing his grandiose vision for Vizcaya to fruition. (More than ten percent of the Grove’s population were hired to work on the villa over a three-year period).

Despite the millions, he was seeking something beyond reach: an earthly paradise, a private utopia. He personified an American type–lonely bachelor inside colossal mansion–and he lived out a very Gatsbyesque kind of American tragedy. In December 1916, Deering hosted a Christmas party to celebrate the completion of the big house at Vizcaya. His guests came dressed as Italian peasants and were greeted by a 2nd-century statue of Bacchus, god of wine and fertility, standing guard over a Roman marble basin. An impassioned, almost obsessive collector, Deering had made repeated trips to Europe with his friend and design advisor Paul Chalfin. They purchased whole villages, monasteries, ancient villas, gathering art, extravagant furnishings and architectural relics and shipped it all back to Florida.

The guests walked through chambers festooned with Renaissance tapestries, paintings, Baroque and Rococo carvings, and came out onto a broad limestone terrace that looked out over Biscayne Bay. And it was true. Deering arrived in a gondola, stepping onto the landing like a Medici, while miniature antique canons fired a salute, and Chinese lanterns flickered in the trees, and the discretely hidden orchestra struck up a festive tarantella.

Deering’s half-brother Charles, the art patron, attended the party, as did the painter Gari Melchers and his wife Corinne, the Swedish artist Anders Zorn, and silent film stars Lillian Gish and Marion Davies. Mrs. Gaston Drake, Miami socialite, came wearing a multi-hued dress with velvet bodice, linen headscarf and holding a gypsy tambourine that she rattled whenever being introduced. F. Burrall Hoffman, architect of record, kept to himself in a back room, chatting with Phineas Paist, gaunt-faced associate who did most of the drawings for the villa, while under the sometimes tyrannical direction of Paul Chalfin, who was also there, fussing and fretting with the staff, making sure that the festivities went according to plan.

Deering himself came gliding up from the landing and stood like a statue in the center of the grand foyer, greeting guests, but saying very little, frustrated that the gardens weren’t finished. In fact, it would take another seven years before Vizcaya’s grounds were complete. The intricate geometries of the formal gardens were laid out with marble retaining walls and elliptical parterres, interspersed with sunken gardens, classical follies, ceremonial urns, secret grottoes made of coral, imbedded with seashells, and a 200-year-old fountain designed by Filippo Barigioni that Deering imported from Italy. Subtropical species––strangler figs and ancient oaks––were transplanted from the Everglades, and mixed in with boxwood mazes, orchids, Bitterbush, lilies, and lush banks of Maidenhair ferns. (The rarest plants are were cultivated in a greenhouse that Deering built at the other end of the property).

“I glimpse a high belvedere, a palm-grit grotto, a balustraded terrace of dolphin fountains, Tuscan-tiled loggias, vine-shaded pergolas”, writes Cecil Roberts after his visit to the palatial estate. “Stone windows reveal the arabesques of Spanish, the pointed arches of Venetian-Gothic, the crenellated brickwork of Florentine architecture…” It beggars the imagination and demands comparison with Kubla Kahn’s Xanadu. There’s even a large, man-made lagoon with picturesque little islands and a Venetian-style bridge that leads to an enchanting belvedere on the water’s edge.

The most unusual artifact of all was the “Italian Barge”, a 158-foot-long folly that sat out in the bay, in front of the main villa, like a grounded ship, ingeniously designed to function as a breakwater. Paul Chalfin had suggested “baskets of sea fruits and trophies of sea treasures,” but Alexander Stirling Calder, the Philadelphia sculptor, had surpassed all of that. He carved the barge from oolitic limestone with every manner of fish-tailed sea serpent, mermaid, caryatid, sea nymph, tritons, obelisk and gushing fountain.

JOHN SINGER SARGENT

In February 1917, less than two months after Deering’s gala, John Singer Sargent, the famous Anglo-American painter, is working on the final panels of his “Triumph of Religion” murals at the Boston Public Library. The work is exhausting and Sargent is still recovering from influenza so he decides to take a break and travel to Florida. First, he goes to Ormond Beach to paint a portrait of John D. Rockefeller. Then he continues south on Flagler’s East Coast Railway to Miami where he stays with his old friend Charles Deering, on Brickell Point. Charles is the older half-brother of James Deering, a wealthy businessman in his own right, art patron, and amateur artist who has known Sargent since their student days in Paris.

But, 61-year-old Sargent is restless in the slanting Florida light. His doctor advised him to stop work and recoup his strength, but the painter finds it impossible to accommodate the lazy routines of his host who spends most of the day lying in a hammock. Charles finally takes his guest to meet his famous half-brother and see the villa. Sargent becomes enchanted with Vizcaya and ends up spending more time there than at Charles’s place. It reminds the painter of his favorite sites in Europe that have become inaccessible because of World War I.

Sargent meets Lilian Gish, silent-screen star, at the Vizcaya swimming pool one afternoon and they talk about motion pictures and art. He is not impressed, surprised by how small and frail the actress appears in person. He paints the Greek statues that flank the entryway with deep shadows falling across the surrounding oaks and casuarinas. He paints the spiky fronds of the palmetto plants. By the next week, he has ventured out to the surrounding hammock with its jungle-like foliage and he notices a group of African-American laborers who are working on the “Mound”, a sloping earthwork near the western end of the property. They are young, well-built men from the Bahamian community of West Grove.

Sargent paints them in a series of homoerotic compositions, loosely drawn, colored with fast strokes of pigment, blurred and bleeding around the edges. The men’s muscular physiques are naked in the glaring sun, lying about in the languorous heat, along the beach, or alone, recumbent in the shade, or leaning over a lily pond. Semi-classical in style, they are also sensual, furtive and slightly forbidden in content, and at first he doesn’t show them to his host, but keeps them in a separate folio.

“It is very hard to leave this place”, writes Sargent to his cousin, Mary Newbold Patterson Hale. It’s late March. He’s been in the Grove for more than a month. His Boston clients are anxious, calling for him to return and finish the library murals, but he demurs. He lingers. “There is so much to paint here”, he writes. “Coconut Grove and Vizcayacombine Venice and Frascati and Arunjuez, and all that one is likely never to see again. Hence this linger-longering…”

Before leaving, Sargent paints a watercolor portrait of his gracious host, Deering himself, sitting in the Italianate foyer, light glancing off his receding hair and spectacles. The background is dark olive, burnt umber shadow, in contrast to the glowing foreground of starched white shirt and linen suit. Deering, the quiet American aristocrat, has a commanding presence, but Sargent also understands the follies of wealth and captures something in the face, something forlorn, a far-off look as if questioning, the mouth slightly pinched with impatience or is it discontent, an impending sense of mortality? (Deering is well aware of the disease that will kill him in another few years).

WHITE ROSE: 1922

The Grove is officially incorporated as a municipality in 1919 and the spelling is updated from “Cocoanut Grove” to the more conventional “Coconut Grove”. A new headquarters for the Housekeeper’s Club is built on the corner of South Bayshore Drive and McFarlane Road. The building, designed by Walter De Garmo, is a basic box with a curving gable roof, rough limestone walls and arched windows. The club raises funds to help the plight of exploited Seminole indians, and sponsors the “Alligators”, the first Girl Scout troop in southeast Florida.

In December 1922, two sisters named Myrtie and Gertie, come by train from a suburb of Indianapolis to spend their winter vacation at “Glenwood”, an ivy-covered bungalow overlooking Biscayne Bay. They bring their Kodak Cartridge Premo, a 32×44 mm format box camera, and document every aspect of the trip. Myrtie poses beside a stuffed alligator. Gertie feeds a live turkey named “Vincent”. Both go fishing with Captain Jasper B. Vreeland and display their catch at the yacht club. During an outing into the “Floridian Jungle”, Myrtie and Gertie pose in front of an ancient banyan tree and are particularly fascinated by the strangler fig (ficus aurea), and the way it spreads its tentacle-like roots across the limestone rocks.

By chance, Myrtie and Gertie meet President Warren Harding who has comes south to escape the cold and a political scandal that’s been brewing in Washington. He gives a speech in the Grove, goes fishing at the Cocolobo Cay Club, and has himself photographed with Myrtie and Gertie on the esplanade. (“As posed for me”, writes Myrtie on the back of one shot).

A few days later, the peripatetic sisters stumble across D.W. Griffith, the great Hollywood director, who’s in the Grove to shoot his latest feature: The White Rose, starring Mae Marsh. The 12-reel silent movie is a scandalous potboiler with illicit lovers, philandering clergy, an illegitimate baby, and an attempted suicide. Marsh plays Teazie, a pretty young orphan who falls for Joseph, a recently ordained minister played by Ivor Novello, the British screen idol.

Griffith shoots some of the scenes in the tropical hammocks of the Grove with sunlight shimmering off of Marsh’s wavy locks. Other scenes are shot along the beach, or in front of the Congregational Church on Devon Road. Griffith looks dapper in a three-piece suit, barking directions through a megaphone to crew and cast. Billy Bitzer, Griffith’s longtime cinematographer, invites Myrtie and Gertie to look through the lens of the camera, and they meet Novello and other members of the cast. Back in Indianapolis, a few months later, the sisters select 98 of their favorite gelatin silver photographs and mount them in a leather-bound album. Gertie glues the black-and-white prints into the album while Myrtie writes lengthy captions in graceful, swirling penmanship.

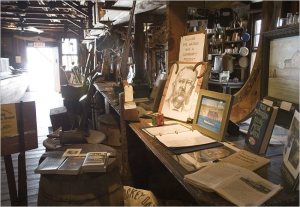

KAMPONG: 1923

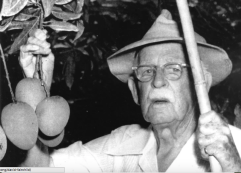

David Fairchild converts Dr. Simmons’ former clinic into a laboratory and surrounds himself with plant samples, books, maps and horticultural charts. This is where he will document, cross-fertilize, photograph, and write about his botanical subjects with increasing devotion. At the main gateway he plants a banyan (Ficus benghalensis) that stands guard with veils of shaggy air roots, threads, and shoots. Further into the property there are jackfruit, Talipot, mango trees and cycads interwoven with bell-shaped figs, ant trees, succulents with frazzled white threads, Soursop, the flamboyante from Madagascar, a swelling baobab from Tanzania, the Ashok or so-called “sorrowless tree” from Southeast Asia, and carpets of tiny flowers leading down to the saltwater inlet.

Fairchild’s wife, Marian, is the daughter of Alexander Graham Bell, and the famous inventor often visits the Kampong. He stays in the old jelly factory that Albion Simmons built on the Kampong grounds. Even in old age, Bell finds it impossible to relax and do nothing. During one visit, he invents a desalinization system, a “Sun Still”, for ship-wrecked sailors, and takes an interest in the biological anomalies of the manatee (trichechus manatus), the “sea cows”, that abound in Biscayne Bay but are becoming endangered as fishermen prize them for their meat, which is said to tastes like pork. Bell publishes a study in The Journal of Heredity, urging for their preservation and encouraging the state of Florida to declare the manatee a protected animal. Bell dies later that summer at the age of 75.

Against the residents’ will, Coconut Grove is annexed to the City of Miami in 1925. Over the next fifty years, there are ongoing efforts to de-annex the Grove. A hurricane with sustained winds of up to 150 mph rips through south Florida in 1926, causing $78 million of damage, and destroying many of the plants that Fairchild planted at the Kampong.

VOICE OF THE RIVER: 1926

Marjory Stoneman Douglas, author, conservationist, and social activist, spends most of her life in the Grove. In 1915, after a brief marriage, she gets divorced and moves to Florida to live with her father, Frank Bryant Stoneman, Editor-in-Chief at the Miami Herald. In 1926, she builds a modest cottage of her own, at 3744 Stewart Avenue. “I didn’t need much of a house, just a workshop, a place of my own”, she writes in her autobiography, Voice of the River. “All I wanted was one big room with living quarters tacked on. I knew an architect, George Hyde, who drew up some plans. He mostly built factories, which was fortunate, because I hoped my little house would be as stout and as sparse as a factory with not much to worry about.”

The house is built in an eclectic Tudor style with rustic hand-split timbers, stucco walls and hardwood floors. The roof is clad in cedar shingles set in wavering lines to resemble thatch, with overhanging eaves to block the sun. There is no driveway because Douglas never owns a car or learns to drive, and there’s no air conditioning or dishwasher. She never remarries, finding her work as a writer and activist more important “than getting tied up with a man”. She lives alone with a cat for the next 72 years, until her death at the age of 108. It’s here that she writes The Everglades, River of Grass (1947), her most enduring work that effectively changes the perception of the Everglades from being a worthless swamp to a unique ecological system. Douglas receives the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Clinton in 1993 and her cottage is designated a national historic landmark in 2015.

Only four years after D.W. Griffith’s visit, Hollywood comes to the Grove again in the form of the Player’s State Theater, a movie cinema that Irving J. Thomas and Fin L. Pierce build on the corner of Charles Avenue and Main Highway. The building is a Mediterranean-style confection with twisting columns, striped canopies and an ornate fountain in front of the cantilevered marquee. It’s ironic that the first movie shown, premiering on January 1, 1927, is Griffith’s own Sorrows of Satan starring Adolf Menjou and Carol Dempster. The movie is based on a novel by Marie Corelli and tells the story of a young writer who sells his soul for financial success.

Every seat is full on opening night. Arnold Johnson conducts Hugo Riesenfeld’s musical score with a 12-piece orchestra. Celia Santon plays the Wurlitzer Concert Grand, one of the largest organs in the country. The 1,130-seat theater operates as part of the Paramount chain, and shows popular silent movies until 1929 when it installs speakers and shifts to sound. Despite initial success, however, the theater struggles through the depression years and finally goes out of business in the mid-1930s. The building is boarded up and lies vacant for the next twenty years.

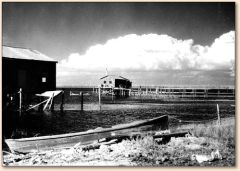

DINNER KEY: 1934

Despite an economic decline in the aviation business, Juan Trippe’s Pan American Airway System (PAA) expands throughout the Great Depression, and holds a virtual monopoly on overseas air travel. In 1931, Trippe introduces the Sikorsky S-40 “American Clipper”, amphibious flying boat, with a range of 950 miles. In 1934, he moves PAA’s Miami hub from the 36th Street airport to Dinner Key in the Grove, taking over the old Naval base and turning it into a million-dollar seaplane station. It is the most technically advanced and most luxurious airport in America.

An allée of Royal Palms leads to the three-story terminal designed by New York architects Delano and Aldrich. The Art Deco building features cream-colored stucco walls, dark blue trim and a terra-cotta frieze that incorporates PAA’s logo into its design. People flock to Dinner Key just to watch the hydroplanes flying in from Cuba, and to see the wealthy passengers and an occasional celebrity, disembark. It is pure theater. “The terminal is a rendezvous for presidents, princes and movie stars of the world, flying down to Rio and other parts”, reads the Pan American brochure. Porters are dressed in navy-style uniforms, and lead the passengers into the sumptuously decorated concourse. The coffered ceiling is decorated with iridescent signs of the zodiac, and a large globe of Planet Earth rotates at the center of the booking hall.

PENCIL PINES: 1940

During the 1930s, poet Robert Frost and his wife Elinor rent a quaint cottage on Avocado Avenue, not far from the Congregational Church. Elinor dies in 1938 and despite the loss of his beloved wife, Frost continues to visit the Grove and in 1940, at the age of sixty-six, decides to build his own house. He buys five acres on SW 53rd Avenue for $1,500 and builds a home out of two prefabricated Hodgson US Assembly cottages that are shipped down by rail from New England. Ralph Lamb, a local carpenter, bolts the kit-of-part sections together and connects the two structures with a picket fence. Frost names his new winter refuge “Pencil Pines” after the tall thin Dade County pines that grow on the property.

Frost does all of his own gardening. he goes to David Fairchild at the Kampong for advice on what and when to plant. Fairchild gives him seeds and cuttings from his experimental garden. Frost clears the land and builds a wall out of rough limestone rocks. Journalists from Life magazine come and take photographs of the white-haired poet working on the wall and run quotes from his famous Mending Wall poem: “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall…”

Soon after moving into the house, Frost suffers the agony of his 38-year-old son, Carol, committing suicide. He lost his wife and now his son. Frost writes frequently about death, what he calls “the abyss”, but finds solace in working outside with his hands, cutting trails through the woods at the back of the property, planting orchids, mango and avocado trees closer to the house. He mulches and fertilizes all of the plants himself and calls himself a “Florida farmer”.

Frost teaches a seminar on poetry and gives lectures at the University of Miami. On weekends, he gives tea parties and cookouts at Pencil Pines for neighbors and friends. He works on his post-Elinor/post-Carol collection of verse, scratching the poems out in long hand with a Schaeffer fountain pen, then typing them up on an old manual typewriter that makes a loud clacking sound. Frost reads the new poems out loud to his students, describing the work as a “modest description of America”. He attends a theatrical event featuring Bea Lillie at the Grove Playhouse wearing a pale-blue jacket and canvas shoes without socks. On Sundays, he often goes for lunch at the Surf Club on Miami Beach with his friends Annette and Hervey Allen. After lunch, they take long walks along the beach.

Later that winter, Frost’s daughter Lillian and grandson Prescott come south and move into the smaller of the two cottages. Fellow poet, Wallace Stephens, stops on his way from Hartford to Key West and visits his old friend. Sitting together in the front parlor, Stephens reads from “Nomad Exquisite”:

“As the immense dew of Florida

Brings forth

The big-finned palm

And green vine angering for life…”

Frost continues to spend his winters at Pencil Pines until the time of his own death in 1963.

WAITING FOR GODOT: 1956

George Engle, a wealthy oilman from Kentucky, buys the derelict cinema for $200,000. He hires architect Alfred Browning Parker to turn it into a performing arts theater with a proper stage for dramatic productions. Engle is a flamboyant character with a vision: he intends to bring “Broadway to Coconut Grove”, and spends more than $700,000 turning the old Playhouse into one of the top regional theaters in America. “George just wants to do something good for the community,” says his wife Dorothy. Architect Parker restores the thirty-year-old structure and simplifies it, removing some of the wedding-cake ornamentation from the facade, re-plastering and painting the walls a Robin’s egg blue. He expands the lobby and adds cheery striped awnings over the main entry.

Opening night, January 3, 1956, features the U.S. premiere of Waiting for Godot, Samuel Beckett’s two-act tragicomedy. Bert Lahr and Tom Ewell play the characters Vladimir and Estragon. The set is a bare, end-of-the-world landscape with a single leafless tree and a rock. Hardly anything happens. Vladimir and Estragon are waiting around for someone named Godot, but he never appears. The 1,130-seat theater is packed.

It’s a coup for Engle and a most auspicious moment in the cultural history of Coconut Grove. A miniature oil derrick spews rum punch at the after-party reception as Engle and his wife greet their guests. Godot is the hottest, most controversial play of the period, and even though it receives luke-warm reviews in the local press, the performance puts the Playhouse on the national map as a place of serious theatrical intent. A few weeks later, Tennessee Williams stages a revival of A Streetcar Named Desire with Tallulah Bankhead playing Blanche DuBois, and after a month of sold-out performances, the production moves to New York. A few weeks later, Engle takes Marlon Brando to the Playhouse to see Bea Lillie perform her one-woman comedy. Brando is at the peak of his fame and gets mobbed by a group of teenage fans.

• • •

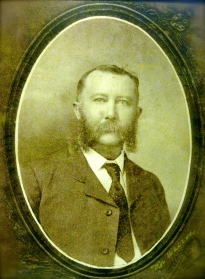

A 19th-century phrenologist would read Watson’s high, broad forehead as obdurate, stubborn, willful and prone to outbursts of violence. The pronounced ears were said to signify lude passions according to Owen Squire Fowler, phrenologist and octagon-house pioneer, but the mouth and jaw are impossible to read because Watson sported such a thick moustache and mutton-chop sideburns as if to conceal his true, ornery nature. Were his lips full and fleshy or were they thin and coldly pursed? Did they smirk with an ironic foreshadowing of his own demise or were they locked in a permanent frown? It’s hard to tell.

A 19th-century phrenologist would read Watson’s high, broad forehead as obdurate, stubborn, willful and prone to outbursts of violence. The pronounced ears were said to signify lude passions according to Owen Squire Fowler, phrenologist and octagon-house pioneer, but the mouth and jaw are impossible to read because Watson sported such a thick moustache and mutton-chop sideburns as if to conceal his true, ornery nature. Were his lips full and fleshy or were they thin and coldly pursed? Did they smirk with an ironic foreshadowing of his own demise or were they locked in a permanent frown? It’s hard to tell.