“I think we are in the rats’ alley Where the dead men have lost their bones.”-T.S. Eliot

Someone was barking through a megaphone: “Keep moving … not too fast.. don’t look at the cameras…” and we were told to walk deeper into the sandy pit, slowly, towards a group of people wearing black plastic capes at the bottom of the slope. We wore pink buttons that read: “GAS – I AM A HAPPENER” and blew whistles as we marched downward towards a sandy cliff and stacks of multi-colored oil drums that were pushed from a ledge. Then we were told to roll them back up the slope through the sea of fire-fighting foam. I guess I was too young to pick up on the sexual allusion at the time, but the foam felt oddly comforting as it oozed around my ankles and bubbled up to my waist, making me want to pee in my pants. Mud stuck to the drum which made it all the more difficult to roll it up the slope, but I kept pushing because there were men with movie cameras and I was going to be on TV!

Even though I was only fourteen year old, I sensed a topsy-turvy shift in the mood of the day, an altered state of perception.

What’s easily forgotten today is the pre-digital fizz of untethered space and effervescent spontaneity that bubbled everywhere in the late 1960s, in the street, on campus, in mini busses, geo-domes and communes and even in outer space with Apollo astronauts bouncing through the gray shadows of the moon. It started somewhere in a whorl of swirling lines and color emanating from the source, pulsating, protoplasmic, spiraling outward like one of Jung’s mystic mandalas. Suddenly the air was charged with an ineluctable sense of gathering as in a storm brewing or the threads of a fable being woven around an ancient fire. My first inkling of something different, something unpredictable, came, oddly enough, at the East Hampton Town garbage dump in the Summer of 1966, Summer of the Happening.

Happening #3: descending through foam, blowing whistles, Garbage Dump, East Hampton, NY, August 6, 1966 (AG in red circle)

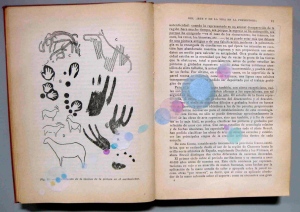

Years later I learned that this wasn’t as spontaneous an event as I had imagined. A New York artist named Allan Kaprow orchestrated this and several other happenings in the Hamptons area, all scripted and produced for a CBS show called “What I Did On My Vacation.” As defined in the Columbia Encyclopedia, a happening is an “artistic event of a theatrical nature, but usually improvised spontaneously without the framework of a plot.” Kaprow himself had coined the phrase back in 1959 with his ground-breaking “18 Happenings in 6 Parts,” a melange of sensual experiences that verged on street theater and broke from conventional art boundaries. To the younger generation of artists, including Kaprow, Jackson Pollock’s ritual splatterings (as captured on film by Hans Namuth) seemed more important as performance than conventional painting. Noteworthy happenings of the period included Claes Oldenburg’s “Store” (1961); Robert Rauschenberg’s “Map Room II” (1965); Robert Whitman’s “The American Moon” (1960); and Kaprow’s own “Calling” (1965). These early happenings were precursors of the performance art that would come into fashion twenty years later.

The Hamptons were already in the process of change. The old WASP gentry of the Maidstone and Meadowbrook clubs were giving way to a much more flamboyant summer crowd. The first real auger of disruption came on August 31, 1963 when a debutante party for socialite Fernanda Wanamaker Wetherill turned into an all-night bacchanal. Affluent young guests rioted and practically destroyed an ocean-front mansion in Southampton. Windows were smashed, people literally swung from the crystal chandeliers and a grand piano was shoved onto the beach and destroyed. The party, a spontaneous kind of Ur-Happening without any art critics in attendance, made front-page headlines and marked an end to Social Register ways. There were reports of pot parties on the beach and free love in the dunes. Mitty’s, the first discotheque on the East End, opened in Watermill. L’Oursin, a club that featured psychedelic light shows, opened in the North Sea area. Then came the happenings, transforming the quiet summer enclave into a multi-media event.

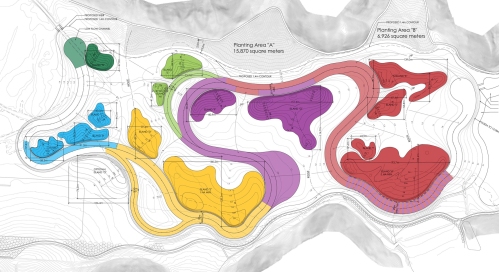

Locations were scouted beforehand. “Picture that dump yard for cars–the one on the way to Springs,” said Kaprow. “I want to have beautiful little children eating picnic lunches in the cars there… Something unthinkable and strange-and magical!” An announcement was made at East Hampton’s Town Hall, and the organizers ran ads in the East Hampton Star and other papers.

It started on Friday, August 5, with a parade at the Southampton railroad station. People pushed oil drums down the street. Others carried weather balloons inflated with helium. A woman was dressed up as “Miss Liquid Hips” in a silver skating costume with white Courréges boots and a space helmet. She stood atop a homemade hover craft and floated down the street. Kaprow himself was dressed as the “Neutron Kid” in a black plastic poncho and World War I aviator’s helmet, riding his own strangely menacing hovercraft device. It was incredibly loud and threw up gritty clouds of dust and sand.

Happening #1: Allan Kaprow as “Neutron Kid” driving hovercraft device, Friday, August 5, 1966, Southampton, NY (near RR station)

The flyer for the next afternoon’s events read:

Gas – A Happening

Place: Amagansett Coast Guard Beach

Date: Saturday, August 6, 1966

Time: 2:30-3:30 PM

Procedure: Children and adults may help

release helium balloons, frug on the

beach, help to start plastic skyscraper,

swim.

Two different rock bands were playing simultaneously, but there was a technical glitch and no one could figure out how to get the generators working. One band finally got going and played a strained rendition of the Stone’s “Satisfaction.” Girls in bikinis danced the Frug while giant helium balloons were released into the sky. A skywriting plane flew overhead and spelled out the word “A-R-T” in giant letters. Everything was going according to plan when a red smoke bomb exploded and four skydivers jumped out of an airplane. They were supposed to parachute onto the beach but two of them were blown out to sea and almost drowned. A group of young men paddled out on surfboards and rescued them. For seven-year-old Eric Kuhn the day started off just like any other. “I didn’t know my first Happening was even happening,” he said. “A magnetic flow of people moved eastward along the shore and I followed them towards this giant black inflatable thing.”

This, the “soft skyscraper,” was being inflated by four vacuum cleaner engines but it took a long time as the tower waved flaccidly back and forth, and there was much comment and sniggering from the crowd. “The fun is in the struggle,” remarked art critic Harold Rosenberg who happened to be standing nearby. The inflatable finally reached its fully erect position for a few spectacular moments before toppling over and exploding. Then, in a Lord-of-the-Flies moment, it was torn apart by a group of young boys.

On Sunday morning there was a happening at the Shelter Island South Ferry. Kaprow’s idea was to have nurses in white uniforms (recruited from Southampton Hospital) beckoning like sirens from the ferry slip. They pulled a big black curtain across the slip and cars coming off the ferry had to drive through the curtain. The nurses then climbed into hospital beds that were parked in the middle of the road.

Happening # 4: Nurses from Southampton Hospital stand behind black curtain, waiting for the Shelter Island Ferry, Sunday, August 7, 1966

Later that same day another happening, the final act, was staged out at Montauk Point. Fire-fighting foam spilled down the cliffs and onto the beach. I arrived late but made it in time to run through the foam on the beach and say hello to Kaprow who was supervising. This, in many ways, was the most lyrical and painterly of all the happenings and of all Kaprow’s pieces that weekend, felt most like a tribute to Pollock’s spirit: overlapping lips of foam descending and engaging with the landscape, streaming over the ridges and outcroppings of rock and dirt, the stoney beach, waves rolling ashore, foam meeting foam.

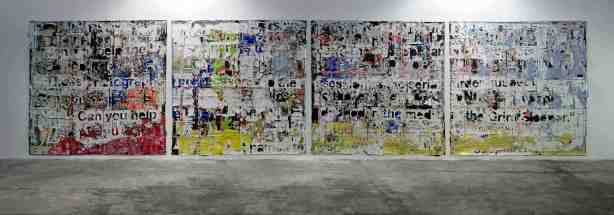

Time magazine later described the Hamptons Happenings as a “combination of artists’ ball, carnival, charade, and a Dadaesque version of the games some people play.” Each event was loosely scripted and open to free-form elements of chance, but at the same time Kaprow’s happenings had to be coordinated within a fairly tight agenda for CBS. (The budget was more than $30,000.) In the end, Kaprow was disappointed by the general lack of spontaneity. “I was looking for more surprises, and everything came out very orderly,” he said.

Time magazine later described the Hamptons Happenings as a “combination of artists’ ball, carnival, charade, and a Dadaesque version of the games some people play.” Each event was loosely scripted and open to free-form elements of chance, but at the same time Kaprow’s happenings had to be coordinated within a fairly tight agenda for CBS. (The budget was more than $30,000.) In the end, Kaprow was disappointed by the general lack of spontaneity. “I was looking for more surprises, and everything came out very orderly,” he said.

I wasn’t aware of any of this at the time. To me, the foam and balloons and plastic inflatables were all a kind of fairy dust, a hint of wilder things to come…

• • •

![215_NBW_ch4_037[1A]_master_med](https://alastairgordonwalltowall.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/215_nbw_ch4_0371a_master_med.jpg?w=427&h=288)