“The Taoists say ‘hug the earth, embrace the sky’,” said Norman Jaffe, sitting in the fourth booth back at the Candy Kitchen in Bridgehampton. It was the first time we had met, and I was surprised by the childlike intensity with which he spoke, not what I’d expected from an architect known for his flamboyant and expensive beach houses. I ate my grilled-cheese sandwich while Jaffe explained something about the new sanctuary at the Jewish Center. It was 1985, mid-week, late autumn, and there were only a few other people having lunch that day.

While describing the project, Norman drew a sketch on the back of an old manila envelope explaining how the rabbi would stand at the center and be surrounded by the congregation on three sides. This, in turn, lead to a discussion about sacred space, the ancient stone circles of Britain, Gothic cathedrals and how Muslim architects diffused light across the ceilings of their mosques. We had both read Mercia Eliade’s essay about the symbolic “break in space” and how it defined man’s place in the universe. There was also mention of Louis Kahn’s love of light as “giver of all presences,” and how shadows belong to light; and Songlines, Bruce Chatwin’s book about aboriginal space.

The lines of our own conversation split into other directions and moved from religious architecture to beach erosion, Hollywood Noir and over-development in the Hamptons. (I still have the scrappy notes I took at that first meeting.) Over the next few years we would meet several times for similarly non-linear discussions.

The lines of our own conversation split into other directions and moved from religious architecture to beach erosion, Hollywood Noir and over-development in the Hamptons. (I still have the scrappy notes I took at that first meeting.) Over the next few years we would meet several times for similarly non-linear discussions.

For Jaffe, architecture, especially residential architecture, was not a detached, scientific investigation so much as a “romantic journey.” He believed in the transformational powers of a house, like Wright who wrote of the “fire burning deep in the masonry of the house itself,” and was convinced that domestic architecture stood at the very core of the American experience. He was open to every imaginable influence from Wright and Piranesi to Kabuki theater, Mayan temples, potato barns and music theory–all combined and synthesized somehow through his own furtive form of alchemy. “Norman’s vision of architecture was as an experience of theater and emotion,” said his son, Miles Jaffe. “What does this thing make you feel like? How do you respond to it?” A former associate put it another way: “He believed that architecture could be a kind of salvation, a magic crystal… a kind of Pythagorean alignment and somehow, out of this geometry, you could open up a door to the other place.”

But Jaffe was very much a product of his image-driven times and intuitively understood the power of imagery over words. He was broodingly handsome and frequently posed for professional photographers. More than one female client, struck by his good looks, recalled Gary Cooper’s portrayal of heroic architect Howard Roark in the Hollywood adaptation of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead. (Some of Jaffe’s presentation drawings bear an uncanny resemblance to Roark’s drawings in that same movie.) He seemed to think in flat, two-dimensional terms, envisioning his houses as set pieces, seen from a single angle, on approach, like the opening sequence of a Hitchock film. He would stalk the perimeter of a site, waiting for something to arise and give him direction. Jaffe made frequent use of the German term zeitgeist, well before it became an overused cliché.

“There are walkers and talkers,” he said. “Talking prevents a building from listening to its site. Walking helps.” After listening, Jaffe would start to draw. He worked quickly, improvising, smudging and rubbing the medium into the paper with his fingers. “The essence of you is Jet Black extra smooth 6325 racing over yellow tracing paper,” wrote one female admirer on his 45th birthday.

“Sometimes I try to seduce the clients with all the graphic facility that I can muster to win their support and fall in love with the projected image I wish them to finance,” said Jaffe, who drew his houses as self-contained objects on the landscape, angular and sloping, with empty lawns or sand dunes in the foreground. His elementary roof forms signified shelter, hearth, and a sense of tranquility and unity that Jaffe seldom attained in his own fragmented life. But it was there on paper as an imaginary place, or destination, however unattainable.

Some of his drawings suggest an inner struggle, a kind of Gothic Sturm und Drang, for which one is unprepared in modernist design, especially in the realm of vacation housing where one expects breezy beach cottages saturated with sunlight and salt air. Others are drawn from an impossibly low vantage, and the houses appear to be looming on a craggy cliff with dark clouds gathering in the background––the proverbial house on the hill––loaded with import and mysterious calculation. Roof planes and overhangs are cantilevered to the extreme, defying gravity, extending to the breaking point. Light and shadow are played against one another for the most extreme effects of chiaroscuro.

Some of his drawings suggest an inner struggle, a kind of Gothic Sturm und Drang, for which one is unprepared in modernist design, especially in the realm of vacation housing where one expects breezy beach cottages saturated with sunlight and salt air. Others are drawn from an impossibly low vantage, and the houses appear to be looming on a craggy cliff with dark clouds gathering in the background––the proverbial house on the hill––loaded with import and mysterious calculation. Roof planes and overhangs are cantilevered to the extreme, defying gravity, extending to the breaking point. Light and shadow are played against one another for the most extreme effects of chiaroscuro.

Most of his clients were upwardly mobile New Yorkers who worked in advertising, publishing, real estate, TV, movie, the fashion and recording industries. Many, like Jaffe himself, were the children of Jewish immigrant parents: urban and cultured, secular and progressive in their politics, but protective of their privacy. “The journey from New York to the Hamptons is a long and arduous one,” said Jaffe who understood the price his clients paid for their success. Most of them lived hectic, stress-filled urban lives and needed quiet places to unwind and lick their wounds. But while they wanted to express their individuality, they also wanted warmth and intimacy, not full exposure and the laboratory-style living of hard-edged modernism.

The standard glass box was too severe for their emotional needs. They wanted domestic space that was charged with meaning and this was a promise that Jaffe tried to fulfill: “I’m dealing in dreams,” he said. “I build houses that are an adventure to live in if the people are qualified for this adventure…” and yes, you had to “qualify” for such an adventure.

The standard glass box was too severe for their emotional needs. They wanted domestic space that was charged with meaning and this was a promise that Jaffe tried to fulfill: “I’m dealing in dreams,” he said. “I build houses that are an adventure to live in if the people are qualified for this adventure…” and yes, you had to “qualify” for such an adventure.

Jaffe knew how to create the comforting illusion of refuge and retreat as well as a sense of “arrival.” His clients loved the romantic, woody feeling of his interiors, his sunken living rooms and stone fireplaces, his sensual use of materials. “The materials of a vacation house should be alive with the snap and vitality of the natural,” he said.

During client meetings, he liked to probe and ask the most intimate kinds of questions. “Norman interviewed me almost as though he was my analyst,” confessed one homeowner. “He wanted to know things like how I felt about being closed in, or the reverse.” In theory, his houses would counteract the nagging sense of urgency that followed them all the way out the Long Island Expressway and infected their weekends. “We try to calm them down,” he explained, speaking as the architect/rabbi/therapist.

During client meetings, he liked to probe and ask the most intimate kinds of questions. “Norman interviewed me almost as though he was my analyst,” confessed one homeowner. “He wanted to know things like how I felt about being closed in, or the reverse.” In theory, his houses would counteract the nagging sense of urgency that followed them all the way out the Long Island Expressway and infected their weekends. “We try to calm them down,” he explained, speaking as the architect/rabbi/therapist.

“They’re busy people; they come to the Hamptons to rest. We don’t clutter up their minds and eyes with a lot of paraphernalia,” as the complexities of late 20th-Century living could be modified by design. But again, as with Wright, he believed in the healing powers of his profession, and if everything came together just so––the angle of the roof, the right combination of materials, the perfect saturation of natural light––there would be a certain lift, a poetic moment that transcended the mundane indignities of city life.

For Jaffe, every commission was a work in progress from inception to completion, and he would keep worrying the problem until the very end. He used to say that “Only God knows how to make four good elevations,” while he, himself, was hoping for two, maybe three, but always made sure to have at least one good elevation. He would rework his drawings with a pre-digital process of collage: splicing together Xerox reductions, cutting out foreground silhouettes and pasting them onto pre-drawn backgrounds, or drawing over photographs to find the right balance of forms.

For Jaffe, every commission was a work in progress from inception to completion, and he would keep worrying the problem until the very end. He used to say that “Only God knows how to make four good elevations,” while he, himself, was hoping for two, maybe three, but always made sure to have at least one good elevation. He would rework his drawings with a pre-digital process of collage: splicing together Xerox reductions, cutting out foreground silhouettes and pasting them onto pre-drawn backgrounds, or drawing over photographs to find the right balance of forms.

Unlike most architects, he saw the construction phase as part of the same intuitive process. For him, there were no sacrosanct lines between “design” and “build.” “When I’m building one of my own buildings, I’m really seeing the work drawn at a larger scale,” he said. He would visit the construction sites on a daily basis, getting to know the workers, lending a hand, moving a slab of stone, choosing the right length of lumber, shaping the landscape with a bulldozer or placing shrubbery in such a way that would highlight the architectural lines. It was a highly articulated process from start to finish.

Jaffe was infamous among Long Island builders for his indecision and last-minute changes. His office would produce official construction documents, but the final decisions were often made on site. When he saw a problem or changed his mind about some aspect of the design, he would simply do a sketch on a shingle or a scrap of sheet rock and hand it to the contractor, explaining how a wall should be moved one way or another, how a ceiling should be dropped another foot, or how the angle of a staircase should be shifted a few degrees. He saw a certain plasticity and flexibility in wood-frame assembly that baffled and infuriated contractors: “Seeing in various stages of framing and sheeting the forms that I had thought of and how I had the opportunity to further express these forms, simplify them, perhaps revise the proportions slightly,” he explained to the uninitiated.

Sometimes he would go to the site of a half-built house, take a sequence of Polaroid photographs, cut and paste together a composite image, then redraw the facade in question and go back to the building site the next morning with a list of revisions. (In many cases he was obliged to pay for these changes himself and would end up losing money.) Work crews joked that they would frame out Jaffe’s houses with light-gauge finishing nails so they could pull it all apart when the architect changed his mind, as he inevitably would.

After construction was completed, Jaffe spent an inordinate amount of time having the houses photographed, finding the single “money shot” that best expressed his original intentions. (In some cases, he drew out detailed directions for the photographers to follow.) Even then, the project was not truly finished. He would revisit his favorite houses to see how they were doing: how the light moved across a certain wall, how the Japanese Black Pines had filled in around the terrace. In one instance, he went by a house with a swimming pool and removed a diving board that the homeowner had installed after the fact. (Jaffe hated diving boards.) In another instance––and again, without consulting the clients––he climbed up on the roof and removed an offending television antenna. “What is the meaning of architecture?” asked Jaffe. “The meaning of architecture for me lies in the collision that occurs between the function of a building (be it a house, a cathedral, a theater, a store, an office building) and the architect’s response to that function, his sense of life.”

After construction was completed, Jaffe spent an inordinate amount of time having the houses photographed, finding the single “money shot” that best expressed his original intentions. (In some cases, he drew out detailed directions for the photographers to follow.) Even then, the project was not truly finished. He would revisit his favorite houses to see how they were doing: how the light moved across a certain wall, how the Japanese Black Pines had filled in around the terrace. In one instance, he went by a house with a swimming pool and removed a diving board that the homeowner had installed after the fact. (Jaffe hated diving boards.) In another instance––and again, without consulting the clients––he climbed up on the roof and removed an offending television antenna. “What is the meaning of architecture?” asked Jaffe. “The meaning of architecture for me lies in the collision that occurs between the function of a building (be it a house, a cathedral, a theater, a store, an office building) and the architect’s response to that function, his sense of life.”

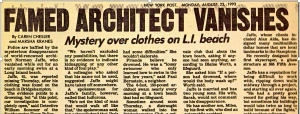

On August 23, 1993, I heard the news of Jaffe’s disappearance and like everyone, was stunned. I had seen him earlier that summer at a Shushi restaurant in Amagansett and he seemed so vibrant, so himself. He left behind a heart-broken circle of friends and family as well as an extensive body of work that has never been fully digested or critically assessed. There’s a lingering sense of unfinished business, as if his legacy will take some time to sort out.  Norman Jaffe never yielded to the role of an architect going about the prosaic business of designing buildings. Architecture for him was, rather, a mysterious means to a less definable end, a lifelong quest to reach another plane of understanding, to find the door and maybe even step through that ineffable “break in space” that we’d discussed in the Candy Kitchen, eight years earlier. Jaffe’s work can best be understood in the light of that quest.

Norman Jaffe never yielded to the role of an architect going about the prosaic business of designing buildings. Architecture for him was, rather, a mysterious means to a less definable end, a lifelong quest to reach another plane of understanding, to find the door and maybe even step through that ineffable “break in space” that we’d discussed in the Candy Kitchen, eight years earlier. Jaffe’s work can best be understood in the light of that quest.

Ten years after his disappearance, I curated a museum retrospective of his work. I also produced a documentary film and wrote a book, but I only grazed the surface. There was so much that I didn’t know and would probably never know. On this, the 27th anniversary of his disappearance, the architect remains an enigma and continues to visit my dreams, a friendly spirit standing in the waves, holding forth a book that I am unable to open or read.

• • •

To learn more about Norman Jaffe, watch “Beyond the Beach: The Life and Death of Norman Jaffe, Architect,” a half-hour documentary by Alastair Gordon:

An earlier version of this essay was published in Romantic Modernist: The Life and Work of Norman Jaffe, Architect, by Alastair Gordon, New York: Monacelli Press, 2005

© Gordon de Vries Studio, 2020

Superb … I’ll be reading more, thank you. Some of the Jaffe houses looked a bit Sea Ranch-y to me. xxx

Get Outlook for iOS ________________________________

Good eye! Jaffe studied with Joe Esherick at Berkeley and worked on some aspect of Sea Ranch with Donlyn Lyndon right after arch. school and before he moved to the east coast. Not sure exactly what he did, but that was his west-coast background.

Dated Joe Esherick’s daughter in my youth and Don Lyndon was my Grad critic in my senior year at Princeton. All familiar and wonderfully talented individuals! Stay healthy and be well,

a break in thr silence

Sent from ne iPad Good morning Alastair, Your essay, ‘new post’ was as always a nice surprise and ‘space stirring’ here in the lockdown at Hazelfield where we like the rest of the world is realing never seenshe before. I don’t think that we fully comprehend the reality how this microscopic parasite has delivered a stunning blow to civilization. Death is hiding in ‘ space’ as you call it, to attack us and no treatment at hand. Even in a garden hoe or or cover on a newsstand mag. ( wonder what Earnest would have had to say in chapel so long ago)

I never heard of Norman Jaffe or his houses as my experiences in the Hamptons were limited exclusively to the Kaplan compound and that of Addy de Menil/ Ted Carpenter.

Somehow the photograph of Jaffe at the outset told me the story was not going to end well and now in view of the unprecedented reach of technology, those Jaffe beach houses have become irrelevant objects trouve no longer possible to comprehend in any kind of understandable, humane context.

A must read article by the anthropologist Wade Davis offers only cold comfort that the ‘fluidity of memory and a capacity to forget’ is one our haunting traits that allows us to deal with unimaginable degradation. His article is called, “The Unravelling of America,”- the end of the myth of American exceptionalism

On another tack, I recommend “Lives of Houses” edited by the great biographer Hermione Lee , papers on how lives of .people end up requiring lives of the houses where u they have lived . Imagine what a challenge those Jaffe houses would pose to a writer- m culturally more remote than those 18th-19th houses Addy moved and reassembled on the beach. She gave them to East Hampton were Robt Sfern et al recycled them as office space for the village.

But enough, ‘ how was the play Mrs.Lincoln?’

Every one is very well. More details anon.

W. H. Adams Hazelfield 1633 Warm Springs Road Shenandoah Junction, W. Va. 25442

whadams@frontiernet.net

>>

Sent from my iPhone

William H. Adams Hazelfield 1633 Warm Springs Road Shenandoah Junction, W.Va. 25442 whadams@frontiernet.net

>

Great piece, Alastair. Your conversational style always draws me in. I love Jaffe’s work, particularly the Gates of the Grove.

Pingback: Introducing Clever Confidential: The Darker Side of Design—The Strange Disappearance of Norman Jaffe » Portal4News

Pingback: The Darker Side of Design—The Strange Disappearance of Norman Jaffe | Sculptor Central

Pingback: The Darker Side of Design—The Strange Disappearance of Norman Jaffe | Sculpture Buzz

Pingback: Introducing Clever Confidential: The Darker Side of Design—The Strange Disappearance of Norman Jaffe - Mashup Design : Web Design Articles & Resources

Pingback: Introducing Clever Confidential: The Darker Side of Design—The Strange Disappearance of Norman Jaffe – Condo & Casa

Pingback: Introducing Clever Confidential: The Darker Side of Design—The Strange Disappearance of Norman Jaffe

Pingback: Crime news Introducing Clever Confidential: The Darker Side of Design—The Strange Disappearance of Norman Jaffe - Welcome to World Editorials News