“Well, as I say, the first contact the Japs made was Ernest Gordon and he got shot up.”

– Captain Bal Hendry

The bedroom is small with barely enough room for a queen-sized bed, a chest of drawers and a chair, but my father seems happy, looking over the luminous waters of Gardiner’s Bay. The name that got us started was Titikarangan. I was startled. While his short-term memory continued to disintegrate, his long-term memory seemed to be getting stronger, and now this odd-sounding name arose from the depths of his subconscious like a magic incantation: Titikarangan. I had never heard of it before, but he said it with absolute conviction. I Googled it and even though my spelling was wrong, the name popped up on a map of modern-day Malaysia, a real enough town in Kedah Province, just to the south of Merbau Pulas.

The battle started early on the morning of December 17, 1941, only ten days after Pearl Harbor. The Japanese were dressed in native turbans, wide-brimmed hats and sarongs and were moving out from the rubber trees and onto the road, as if they might be Malay workers taking flight from the Japanese advance. Everyone was fooled. Lt. Bremmer cried out: “hold fire,” in a loud enough voice for everyone, including the Japanese, to hear, revealing ‘A’ Company’s position and thereby losing the advantage of surprise. (It was the Argylls first encounter with the enemy).

There was a brief moment of hesitation when my father had to remind himself not to run or hide, but the moment passed and he felt a relative sense of calm, considering the fact that live rounds were now buzzing past his head, shredding leaves on the tulip trees. He was fine. The fear was only in his mouth, dry and metallic.

The first wave went down, wounded or dead, or playing dead. Then came another wave, ignoring the crossfire of the Bren guns. “They came crawling through the monsoon drains and crawled into the Lalang grass,” said my father who now realized that the Japanese weren’t the soft targets they’d been ridiculed as being in the Straits Colony press, with buckteeth and bad eyesight. They were fearless and fast, all too eager to run straight up the hill, bearing their chests to the fire, falling willy-nilly.

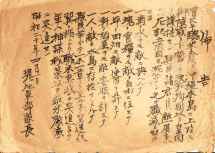

My father got up and shuffled into the bathroom for a pee, but was now sitting in bed again, clear-eyed and remarkably lucid. (Could it have something to do with his Parkinson’s medication?) He told me about the battle with a breathless urgency that I’d never heard before, almost as if he needed to get it off his chest. He began to sketch a map on the back of an envelope with a wavering line for the Karangan River, a double line for the bridge and another, straighter line for the road that ran south through Serai and Terap. (He drew “X’s” to represent each squad, “O’s” for machine gun placements and “M’s” for mortar positions).

The enemy troops were bunched up together, confused and unsure of where to move next and they made easy targets in the cross fire. “We killed more than two hundred during the first assault,” said my father, leaning to one side, while I handed him a mug of tea. The official history puts it closer to a hundred, but it was surprising to me that after all these years of being a Servant of Christ, he was still proud of the number that had been slaughtered that morning.

Now my father could see them scattering, rolling down the escarpment toward the river. They didn’t mind getting killed and they continued to run quite recklessly into the barrage coming from the other flank. There was a brief lull and then another wave came up the hill, even faster this time, making a flanking move to the north. That was their strategy: the deep circling move. The Argylls killed another thirty but that didn’t stop them and my father worried that his men might be cut off and have to fight their way back to Serai or be forced to surrender.

Now my father could see them scattering, rolling down the escarpment toward the river. They didn’t mind getting killed and they continued to run quite recklessly into the barrage coming from the other flank. There was a brief lull and then another wave came up the hill, even faster this time, making a flanking move to the north. That was their strategy: the deep circling move. The Argylls killed another thirty but that didn’t stop them and my father worried that his men might be cut off and have to fight their way back to Serai or be forced to surrender.

The ones who’d been in the vanguard were already down but more kept coming, heads down, carrying Type-92 machine guns, trying to set them up with their clumsy tripod legs, but those men were also shot, and then another squad moved in to take their places and managed to maneuver themselves into a better position. My father was convinced that this was the vanguard of the encircling movement and he felt the urge to move up, laterally, towards the enemy and cut them off before they could gain further ground. One of the Japanese snipers climbed a tree and started firing at an angle across ‘A’ Company’s position. My father signaled L. Cpl Gray and two others to move back behind the sniper which they did but the sniper shot Gray and turned to shoot the others but somehow got his feet tangled in the branches of the tree and Pvt. McEwan was able to shoot him from the other side. (He promptly fell to the ground, dead).

That was about when my father stood up, all six-foot-three of him, and started running, waving two of the jocks–Pte. Logan and Pte. Gibson, he thinks–to follow him as he raced along a narrow footpath that traversed the ridge. (I imagine how he ran that day, with his loping gait, as if he were back on the rugby pitch at St. Andrews, slightly dazed and out of breath, not wanting to fuck up).

All he felt was a ping and numbness in his hand, then a damp red circle blooming on his shirt. “I seem to have been hit,” he said to Sgt. Skinner in the most nonchalant way. Then he couldn’t catch his breath because one of his lungs had been punctured by a 7.7 mm round from an Arisaka machine gun. (The bullet also penetrated the deltoid muscle and shattered part of the scapula and clavicle). His heart stopped, missed a number of beats and started again, rapidly this time and out of rhythm, and that was when he passed out, both knees buckling, his large frame tumbling through space. Was there a second explosion near his feet, or something inside his head unspooling, some neurological fail-safe that created the impression of extracorporeal suspension when, in fact, he was simply dying, going from brightly sparking networks of thought to nothing, apa-apa, as the native Malays called it? Two of the jocks dragged his body around the back of the Cengal tree and that was where he lay for what seemed like hours.

He could see how their legs were bowed out like cartoons and a part of him was still running towards the high point, as if his other body, his wounded body, were still in forward motion after he’d fallen, as if he could still engage and withdraw and recapture the ridge. Was he hallucinating or were there decisions still to be made? Could he fall back to the river, through the kampong and rendezvous with ‘C’ Company with their armored cars on the road to Serai at No. 14 milestone, or to Captain Bardwell of ‘B’ Company who was holding the narrow bridge with three-inch mortars?

He was vaguely aware of black branches on the tree overhead, and he was aware of warring factions within his own nervous system, adjusting to the shock, sending out contrary signals–prepping for death?–and he imagined a network of bifurcating nerve ends, skipjacks and wireworms. He should have seen them coming, re-routing and bypassing the damaged tissue, but he faded in and out and there was an incandescent burst near his head and then another to the west. He could see cassia, stunted palms, ancient mossy angsana around the blurred periphery of his vision. Were those birds or were they bullets? He couldn’t be sure.

Something flies in and away…

He’s dead and someone is coming towards him. There’s no golden stairway or white light, but there’s an oddly pleasant sense of release, of running up Whim Hill behind Aunt Jean’s house, and a ghostly figure standing by the oily tarn off Roxburgh Street where the boys broke bottles. He thinks he hears a woman singing somewhere near the slit trench, a woman’s voice coming from the very heart of the battle, while a slanting part of his consciousness is telling him to wake up and take command.

His soul, or whatever had been flapping its wings outside his body, was suddenly back inside his body and he could move his hands again. He tasted cordite in the air and the sweet nectar of ginger blossom, of being alive, and slipped back into his damaged corpus, suddenly aware of the fact that he was lying in a shallow depression behind the Cengal tree.

The advance was beaten back and the hill was retaken.

Cpl. Boyd of the medical corps sprinkled sulfa into my father’s wound and applied a field dressing. This being Boyd’s first combat casualty, he may have over-injected the morphine, and my father remembers vomiting, tripping on the morphine and experiencing an expanded sense of the infinite, while assuming, once again, that he was being left to die.

The battle was over in less than two hours and the Japanese faded back into the swamps of Perak Province. The Argylls, after calling off their plan for a counter-attack, fell back to Kupang.

Padre Beattie, regimental chaplain saw blood pooling around my father’s neck and assumed he was gone. “Dear Lord, embrace this your servant…” They took him to a dressing station at Terap where he was revived and given a blood transfusion. Two days later he was transferred to Kuala Lumpur and then, during the endless train ride south to Singapore, he began to wonder about the voice that sang to him on the battlefield, just after being shot. There was something familiar about it. (His mother, Sarah, was an opera singer).

As a child, I’d always seen something numinous in the outline of my father’s war wound. It looked like a vaccination mark, but bigger, a circle of crinkled skin, about the size of a quarter. It was his badge of courage, and during the summer, when he went around the beach house shirtless, he would let me touch the damaged tissue with my finger and trace the trajectory of the bullet as it went in and came out the opposite side. The scar was the only tangible connection I had to his war, a one-inch-diameter portal to his past. By touching it, I felt a connection to his pain and suffering.

But my father never spoke about the battle. He never wrote about it, not did he bring it up in his lectures or sermons. I never knew that he was one of the first to be wounded and knocked out of action. I wasn’t so much disappointed as I was surprised because I’d carried impressions since childhood of ongoing battle in jungle conditions with retreat and counter attack over a period of many weeks, even months. But that wasn’t the way it happened. As Bal Hendry, his best friend and succeeding commander of ‘A’ Company, said: “The first contact the Japs made was Ernest Gordon and he got shot up,” stating the facts as they occurred.

We were done for the day. My father turned over to take a nap and ended up sleeping for the rest of the afternoon. I picked up the lunch tray and carried it into the kitchen. It had been a good start. Some door had flipped opened and I wanted more. A few days later, he had a visitor, a woman in her seventies, sniffing around, now that my mother was gone. I didn’t disturb them and let her talk about the old days, but after she left I showed him the book I had bought on amazon.com.

“It says here that your commanding officer yelled at you for getting wounded,” I told him. It was a freshly published history of the Malayan Campaign and as soon as it arrived in the mail, I flipped to the index and found twenty-seven references to “Gordon, Capt. E.”, but it was the passage on page 53 that grabbed my attention: “The wounded Tiny Gordon, a very big man, was assisted back,” I read out loud while my father climbed back into bed, trying to suppress his irritation.

“‘Stewart approached him,'” I continued to read, “‘and according to some accounts Gordon, far from receiving any congratulations for ‘A’ Company’s efforts, was fiercely and very publicly reprimanded…'”

“Nonsense!” cried my father, interrupting, but I ignored him and kept going: “‘…reprimanded for allowing himself to be wounded so early in the battle. A year of jungle training wasted!'”

“Is that true? Were you reprimanded?”

“No! Stewart came around to see me,” he said. “He was concerned.”

“Why would anyone write that if it weren’t true?”

“How should I know? I never received a scolding from Ian Stewart. He only expressed sympathy for my wound.”

According to the author of the book, it was David Wilson, another captain in the Argylls, who’d been the source of the “well-known” story. But why was Wilson telling tales at such a late date? Colonel Stewart didn’t mention anything about it in the official account of the Malayan Campaign that he published in 1947: “About 10.45 hours Captain Gordon, Company Commander, was wounded and Captain Hendry took over.” That was all. He didn’t say anything about reprimanding my father, nor did he criticize any of the actions that he’d taken as commander of ‘A’ Company. Perhaps Stewart was frustrated that he’d lost one of his best officers so early in the campaign. I could understand that and perhaps he said something to my father in a scolding but friendly way: Och, did you really have to go and get yourself shot so early in the day? Something like that which might have been overheard and misinterpreted by one of the men?

After some research, I learned that Captain Wilson hadn’t been anywhere near the battlefield that day. He was 400 miles to the south, at Fort Canning, safely eating breakfast with General Haig’s staff, so why would the author cite him as a reliable witness when he wasn’t even on the scene and probably only heard about the incident second hand, if indeed there had been such an incident in the first place? (Was Wilson harboring resentment against a fellow officer? Had he been passed over in some way?) I wanted to believe my father’s version, but I also felt that there must have been some vestige of truth to the story. Had he screwed up somehow? Disobeyed orders? Shown hesitation or cowardice? I don’t know. I prefer not to think about it. If anything, it made him more existential and human, less of the heroic action figure. I felt ambivalence mixed with curiosity, torn between wanting to stand up for my father, while remaining detached. (Now I understood why he never spoke about the battle. It was complicated.) And anyway, almost everyone involved was dead so I would probably never know the truth.

The photograph was taken early in 1942 against a darkly mottled backdrop at the Imperial Studios on Jervois Road, and it’s signed in the lower right corner: “Best Wishes, Ernest, 21/1/42”, January 21, 1942. On that same afternoon, five RAF Hurricanes were shot down over Queenstown, so there’s an understandable degree of urgency in the eyes, intense but distracted. Yamashita’s 25th Army had reached the Johor defensive line, and the city was under constant bombardment. The morning heat caught the smell of rotting flesh and spread it across the entire harbor area. There were three corpses and a dead horse lying in a ditch near Keppel Road. Mitsubishi bombers were coming in from the east, dropping anti-personnel grenades that exploded overhead and sent deadly shards of metal into the streets.

While everything outside the camera’s frame was chaos, inside the frame he’d conjured up the impression of calm, measured calm, looking straight into the lens, eyes wide open, very awake, alert. It’s amazing to me that he had the time and temerity to walk into a studio on Jervois Road and have his photo taken when, all around, the skies were crashing down. Only five weeks earlier, almost to the day, he’d been shot through the shoulder, but now he wanted to send proof home of his robust state of health. He looks shorn, his hair cropped on the sides but rising over his forehead in dark, glistening waves. He’s lost quite a bit of bulk after three weeks in hospital–the morphine made him sick–which only accentuates his square jaw-line and forehead, yet the lips lie gently across the face, soft and shapely, almost feminine. This would be the last photograph he sent to his parents before the fall of Singapore. They wouldn’t hear from him for another three and a half years.

This is the fifth in a series of ‘discoveries’ about my father’s life. See also:

#1 Reconstructing My Father’s Plane Crash, 1936

#2 Comrades of Night: River Kwai, 1943

#3 Landscape and Trauma: Glen Coe, 1945

#4 Aloft: Pre-War Summer, 1939

Alastair, how is your writing project progressing re memoir of your father’s post-war years?

i always enjoy and am intrigued by the stories you share about your dear father’s life journey.

james

Hi James,

Wish I had a stretch of six months to finish revision, but all parts are pretty much finished. I’ve had a few other books I had to do first, but I’m hoping to publish it within the year…

Hello.

Please, please forgive me for intruding in your private life and memories.

I have read Through The Valley of The Kwai numerous times and am deeply moved, challenged and convicted after every reading. When I am translated to my heavenly home, after meeting Jesus, I want to meet your father.

I do sincerely hope this is not too much to ask nor too painful. May I please have a copy of the photo here of you father? It would mean so much to me. A simple “no” will be most acceptable.

Very, very best and kind regards,

Mike Partyka