I drive south on the parkway and turn off at Exit 98, into rolling fields and a shaded street that skirts a saltwater inlet known as Shark River. The clouds are low and flecked, folded back on themselves like paper sacks, ruffled with iridescent streaks of gray. This must be the place, Camp Evans, surrounded by earthen berms and high, chain-link fencing. A man with a sunburned face waves me inside the former military installation, pulls the gate shut and shows me where to park my car. It’s a ghost camp. Old brick administration blocks, Quonset huts, concrete out buildings are all boarded over and spookily quiet. We walk past rusting equipment and a series  of wood-framed structures with buttressed supports. As soon as we get around the far end of the biggest Quonset hut, I see them: three Dymaxion Deployment Units (DDUs) sitting in a row and a fourth across the way, looking like so many alien pods, with portholes and conical roofs, as if dropped from the sky. I’d driven down from New York on a hunch. There were a few intriguing notes, hand-scrawled in the Fuller archives at Stanford University; then a vague mention on the Internet–one of those “haunted landscape” sites, something about a “corrugated igloo”–but now they were here, standing in front of me, the missing artifacts that Fuller designed in response to wartime housing needs: mass-produced to be easily shipped and assembled and provide shelter in war-torn locations. I‘d heard vague rumors about, but no one seemed sure if

of wood-framed structures with buttressed supports. As soon as we get around the far end of the biggest Quonset hut, I see them: three Dymaxion Deployment Units (DDUs) sitting in a row and a fourth across the way, looking like so many alien pods, with portholes and conical roofs, as if dropped from the sky. I’d driven down from New York on a hunch. There were a few intriguing notes, hand-scrawled in the Fuller archives at Stanford University; then a vague mention on the Internet–one of those “haunted landscape” sites, something about a “corrugated igloo”–but now they were here, standing in front of me, the missing artifacts that Fuller designed in response to wartime housing needs: mass-produced to be easily shipped and assembled and provide shelter in war-torn locations. I‘d heard vague rumors about, but no one seemed sure if  they were still extant or had already been destroyed. Elizabeth Thompson, Director of the Buckminster Fuller Institute, couldn’t confirm their existence, and Allegra Snyder, Fuller’s 86-year-old daughter, had never heard of any DDUs in New Jersey. “I don’t know how many were manufactured in the end, but the DDUs helped break down the notion that living structures had to be primarily rectangular,” she said over the phone from her apartment in Manhattan. “That was quite a revolution in and of itself.” Jay Baldwin, Fuller disciple and author of Bucky Works, not only worked with the master but rescued the only extant Dymaxion Dwelling Machine (AKA “Wichita House”) and direct descendant of the DDU. I met him a month ago in northern California where he and his wife live in a converted chicken coop and he explained how the Butler Company of Kansas City manufactured several hundred DDUs and shipped them to Italy in 1943 to serve as housing for pilots and radar personnel, “like in Catch 22,” he said, but he’d never heard about any being shipped to Jersey.

they were still extant or had already been destroyed. Elizabeth Thompson, Director of the Buckminster Fuller Institute, couldn’t confirm their existence, and Allegra Snyder, Fuller’s 86-year-old daughter, had never heard of any DDUs in New Jersey. “I don’t know how many were manufactured in the end, but the DDUs helped break down the notion that living structures had to be primarily rectangular,” she said over the phone from her apartment in Manhattan. “That was quite a revolution in and of itself.” Jay Baldwin, Fuller disciple and author of Bucky Works, not only worked with the master but rescued the only extant Dymaxion Dwelling Machine (AKA “Wichita House”) and direct descendant of the DDU. I met him a month ago in northern California where he and his wife live in a converted chicken coop and he explained how the Butler Company of Kansas City manufactured several hundred DDUs and shipped them to Italy in 1943 to serve as housing for pilots and radar personnel, “like in Catch 22,” he said, but he’d never heard about any being shipped to Jersey.

Satellite view of Camp Evans showing location of 8 DDUs (Google Earth)

The first solid lead came from satellite images that showed circular blips in and around the grounds of Camp Evans, a former military base in Wall Township, New Jersey. The blips were consistent in shape and color–light brown, beige–and there were at least eight, maybe even nine of these ghostly impressions on the ground. It felt like a new kind of archeology, using Google technology to peer into the past and uncover forgotten artifacts. I wasn’t absolutely sure, however, as they might have been oil tanks or corn silos, but there was a kind of nozzle or cap rising from the center of each roof that resembled the air vents used in the DDU prototype, so I just had to figure out how to gain access to the site. As I peered closer at my computer screen, I thought of those blurry aerial photographs that John F. Kennedy revealed to the public in 1962 as proof of Soviet missile sites in Cuba.

Discovery begets discovery. After a few phone calls, I learned about “InfoAge”, a science museum that Fred Carl and others started in one of the old buildings at Camp Evans. He answers the phone and seems to know everything about the DDUs and has been working on their preservation for several years. He agrees to meet me at the gate and show me around a few days later.

I am completely stunned when I first see them. I’d expected to find only one or two units at the most and now I learn that there are at least nine and maybe more in an another part of the camp that has been fenced off. They are beaten up but beautiful in a funky industrial way. Some are rusting and dented like old garbage cans with ragweed, bull thistle and poison ivy growing out of every orifice. Here and there the original galvanized metal surface shows through. Others seem surprisingly well preserved, perched on circular concrete slabs, painted Army beige with portholes still in tact, eyebrow shades and original Plexiglas in-fills, now gone milky white and fissured like snowflakes. Squat and homely, the DDUs are certainly not as light and graceful as some of Fuller’s other inventions, such as his ubiquitous  geodesic domes, but in many ways they were just as significant, the product of urgent necessity, and in this there was genius, an early manifestation of Fuller’s philosophy of

geodesic domes, but in many ways they were just as significant, the product of urgent necessity, and in this there was genius, an early manifestation of Fuller’s philosophy of

“ephemerization”, doing more with less. “The idea of re-purposing off-the-shelf technology was an important thread in Bucky’s pragmatic approach to design,” said Jaime Snyder, Fuller’s grandson and executor of his estate. “For Fuller, aesthetics were not that important,” said Thompson at the Buckminster Fuller Institute in Brooklyn. “He had a much larger vision and wanted to provide low-cost, mass-produced shelter for everyone. He really believed that a family of four could live comfortably in one of these units.”

Carl, the man who’s showing me around the base used to be a science teacher at the local high school. He bought a property that bordered the western side of the Camp Evans, and grew more and more curious about his mysterious neighbor. Eventually, he learned that the 243-acre site had been a highly classified research center–Field Laboratory #3–where the U.S. Army Signal Corps developed early radar systems including the SCR-270, famous for having detected Japanese aircraft flying over Opana Point, Hawaii, on the morning of Dec. 7, 1941. The camp continued to be used for top-secret research throughout the Cold War years as well. In fact, the highly classified status of the installation is probably the reason that the DDUs have survived all these years. No one even knew they were. When the camp closed for good in 1993, the Army planned to demolish everything and sell the property to the highest bidder, but Carl felt that the legacy of the camp needed to be preserved. He attended a public meeting in 1994 and spoke up. “I proposed a plan to preserve a portion of the site in

Carl, the man who’s showing me around the base used to be a science teacher at the local high school. He bought a property that bordered the western side of the Camp Evans, and grew more and more curious about his mysterious neighbor. Eventually, he learned that the 243-acre site had been a highly classified research center–Field Laboratory #3–where the U.S. Army Signal Corps developed early radar systems including the SCR-270, famous for having detected Japanese aircraft flying over Opana Point, Hawaii, on the morning of Dec. 7, 1941. The camp continued to be used for top-secret research throughout the Cold War years as well. In fact, the highly classified status of the installation is probably the reason that the DDUs have survived all these years. No one even knew they were. When the camp closed for good in 1993, the Army planned to demolish everything and sell the property to the highest bidder, but Carl felt that the legacy of the camp needed to be preserved. He attended a public meeting in 1994 and spoke up. “I proposed a plan to preserve a portion of the site in

honor of its history and use it as a tool to inspire students to learn about science and history,” he said. “But it’s been a long, bureaucratic struggle.” Working with other concerned citizens, state officials, Congressman Chris Smith and preservation groups, Carl was able to stall the Army. “It was like a game of chicken,” said Elizabeth Merritt, Deputy General Counsel at the National Trust for Historic Preservation. “They left us twisting in the wind for several years.” In 1996, the Army conducted a historic resources study that acknowledged the historic importance of the DDUs as well as other structures on the Camp Evans site, yet they were still planning to level the site. “We started asking a lot of questions,” said Merritt. “We reminded the Army of their obligation to comply with federal historic preservation laws and the next thing we knew they backed off.” On April 1, 2004, the military agreed to pass the property– including sixteen buildings on 37 acres–over to the ownership of the local township and county. “It’s an extraordinary success story,” said Merritt.

The DDUs were perhaps the most rudimentary of all Fuller’s prefab housing schemes. They were simple and inexpensive, with ideal specs for wartime production, made from galvanized metal, with Masonite floors and fiberglass insulation. The idea originally seeded itself in Fuller’s mind during a road trip he took through the Midwest with his friend, the novelist Christopher Morley. The primary intent of their odyssey had been to find letters from Edgar Allen Poe thought to be hidden in the attic of an old house on the Mississippi River. They never found Poe’s letters, but Fuller discovered something else while driving back to Chicago through the Illinois farmland. He became fascinated by the metal grain bins that stood at every farmstead along the way, and learned that they

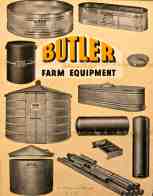

The DDUs were perhaps the most rudimentary of all Fuller’s prefab housing schemes. They were simple and inexpensive, with ideal specs for wartime production, made from galvanized metal, with Masonite floors and fiberglass insulation. The idea originally seeded itself in Fuller’s mind during a road trip he took through the Midwest with his friend, the novelist Christopher Morley. The primary intent of their odyssey had been to find letters from Edgar Allen Poe thought to be hidden in the attic of an old house on the Mississippi River. They never found Poe’s letters, but Fuller discovered something else while driving back to Chicago through the Illinois farmland. He became fascinated by the metal grain bins that stood at every farmstead along the way, and learned that they  were made by the Butler Manufacturing Co. of Kansas City. It was November, 1940, and the papers were filled with news of the London Blitz along with photographs of bombed-out buildings and people sleeping on the street or huddled together in underground tube stations. Fuller began to envision how the Butler grain bins might be converted into emergency housing for the victims of war-torn Europe. Morley, his road companion, encouraged him to approach Butler with the concept and even agreed to fund the research with royalties from his latest novel, Kitty Foyle, which turned out to be a best seller. (An investor named Robert Colgate agreed to underwrite additional costs.) The idea was to retool the production of Butler’s “Long Life” steel bins–“Safe from Fire, Rats, Weather and Waste”–and turn them into bomb-proof shelters for the masses. Fuller went to Kansas City and met with Emanuel Norquist, Butler’s innovative president and drew up an agreement. He then returned to New York and worked out all the specs with his team of architectural associates who included Walter Sanders, a friend and head of the architecture department at the University of Michigan, John Breck, and Ernest Weissman. Their design allowed Butler to use existing dies and required no factory retooling, so the transition into production was relatively seamless. By early 1941 Fuller was making presentations of his “grain-bin house” to the Division of Defense Housing Coordination and other potential clients.

were made by the Butler Manufacturing Co. of Kansas City. It was November, 1940, and the papers were filled with news of the London Blitz along with photographs of bombed-out buildings and people sleeping on the street or huddled together in underground tube stations. Fuller began to envision how the Butler grain bins might be converted into emergency housing for the victims of war-torn Europe. Morley, his road companion, encouraged him to approach Butler with the concept and even agreed to fund the research with royalties from his latest novel, Kitty Foyle, which turned out to be a best seller. (An investor named Robert Colgate agreed to underwrite additional costs.) The idea was to retool the production of Butler’s “Long Life” steel bins–“Safe from Fire, Rats, Weather and Waste”–and turn them into bomb-proof shelters for the masses. Fuller went to Kansas City and met with Emanuel Norquist, Butler’s innovative president and drew up an agreement. He then returned to New York and worked out all the specs with his team of architectural associates who included Walter Sanders, a friend and head of the architecture department at the University of Michigan, John Breck, and Ernest Weissman. Their design allowed Butler to use existing dies and required no factory retooling, so the transition into production was relatively seamless. By early 1941 Fuller was making presentations of his “grain-bin house” to the Division of Defense Housing Coordination and other potential clients.

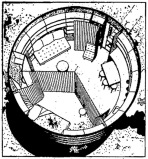

In April, 1941, the first full-scale prototype was unveiled to the public at Haynes Point Park, Washington DC, just across the Potomac from the Pentagon, so that it was easy for military officials to drop by and have a look. Architect Sanders agreed to play  domestic guinea pig and moved into the Haynes Point DDU with his wife and “test-dwelt” it for several days. The press was enthusiastic: “How to be Comfortable Though Bombed,” ran one headline. “A Shelter in War–A Beach House in Peacetime,” ran another. Architectural Forum called it a “dressed-up adaptation of the lowly grain bin” but went on to praise its reasonable cost and demountability, calling it a “three-room defense house, a six-man steel tent,” while hailing Fuller as “prefabrication’s liveliest intelligence.” (AF, June, 1941). The Point Hayes prototype was twelve feet high and twenty feet in diameter with ten porthole windows and fifteen small circular skylights penetrating the conical roof. The interior was lined with wallboard and insulated with fiberglass. Floors were made from 1/8-inch-thick Masonite, and fresh air circulated through an adjustable skylight and ventilator contraption in the center of the roof. As advertised, the DDU cost only $1,250 and came complete with utilities and lightweight furnishings from Montgomery Ward, including a kerosene-powered icebox

domestic guinea pig and moved into the Haynes Point DDU with his wife and “test-dwelt” it for several days. The press was enthusiastic: “How to be Comfortable Though Bombed,” ran one headline. “A Shelter in War–A Beach House in Peacetime,” ran another. Architectural Forum called it a “dressed-up adaptation of the lowly grain bin” but went on to praise its reasonable cost and demountability, calling it a “three-room defense house, a six-man steel tent,” while hailing Fuller as “prefabrication’s liveliest intelligence.” (AF, June, 1941). The Point Hayes prototype was twelve feet high and twenty feet in diameter with ten porthole windows and fifteen small circular skylights penetrating the conical roof. The interior was lined with wallboard and insulated with fiberglass. Floors were made from 1/8-inch-thick Masonite, and fresh air circulated through an adjustable skylight and ventilator contraption in the center of the roof. As advertised, the DDU cost only $1,250 and came complete with utilities and lightweight furnishings from Montgomery Ward, including a kerosene-powered icebox  and stove. Inside it was tricked out with quaint little drapes over the portholes, while a fireproof curtain hung from overhead tracks and could be drawn to divide the interior into four pie-shaped rooms. Openings could be made anywhere in the curving DDU walls to attach additional units as needed, or to install a self-contained “mechanical wing” that Fuller based, in part, on his Dymaxion Bathroom of 1937. He was intent on consolidating all the mechanical necessities of daily living into a single, compact and comprehensive system that would reduce time and cost during installation. Preliminary sketches show a 5-foot-diameter pod, the so-called “toilet wing”, that contained a water cistern, septic tank and gas tanks, partially buried below ground while the roof of the toilet wing was equipped with a windmill to provide enough energy to run a pump.

and stove. Inside it was tricked out with quaint little drapes over the portholes, while a fireproof curtain hung from overhead tracks and could be drawn to divide the interior into four pie-shaped rooms. Openings could be made anywhere in the curving DDU walls to attach additional units as needed, or to install a self-contained “mechanical wing” that Fuller based, in part, on his Dymaxion Bathroom of 1937. He was intent on consolidating all the mechanical necessities of daily living into a single, compact and comprehensive system that would reduce time and cost during installation. Preliminary sketches show a 5-foot-diameter pod, the so-called “toilet wing”, that contained a water cistern, septic tank and gas tanks, partially buried below ground while the roof of the toilet wing was equipped with a windmill to provide enough energy to run a pump. In October 1941, New York’s Museum of Modern Art installed the second DDU prototype in its sculpture garden at 11 West 53rd Street, among its collection of outdoor sculptures. The two-part DDU sat there as an experimental art object, a bombproof art object. “While not proof against a direct hit, its circular corrugated surfaces deflect bomb fragments or flying debris,” explained MoMA’s curator

In October 1941, New York’s Museum of Modern Art installed the second DDU prototype in its sculpture garden at 11 West 53rd Street, among its collection of outdoor sculptures. The two-part DDU sat there as an experimental art object, a bombproof art object. “While not proof against a direct hit, its circular corrugated surfaces deflect bomb fragments or flying debris,” explained MoMA’s curator  of Architecture and Industrial Design. It was an auspicious time for such an installation. Europe was embroiled in violent conflict and although the U.S. was still at peace, most Americans assumed that war was imminent. “This is a house in which to brave bombs,” wrote art correspondent Margaret Kernodle, while Fuller himself pointed out that a round house was easier to camouflage from air attacks. “It coincides with nature-forms such as trees and hillocks,” he said. Not only were Americans prepared for war, but they would face it with a certain amount of artistic flair. Less then two months later, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, making Fuller’s design seem all the more prescient.

of Architecture and Industrial Design. It was an auspicious time for such an installation. Europe was embroiled in violent conflict and although the U.S. was still at peace, most Americans assumed that war was imminent. “This is a house in which to brave bombs,” wrote art correspondent Margaret Kernodle, while Fuller himself pointed out that a round house was easier to camouflage from air attacks. “It coincides with nature-forms such as trees and hillocks,” he said. Not only were Americans prepared for war, but they would face it with a certain amount of artistic flair. Less then two months later, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, making Fuller’s design seem all the more prescient.

Bucky Fuller assembling DDU at the Museum of Modern Art, October 1941

Several hundred units were purchased by the US Army Signal Corps and shipped to bases in the Mediterranean, the Persian Gulf and the Pacific where they were used as housing for pilots, radar crews and aviation mechanics. At least a hundred units were also shipped to Signal Corps bases within the United States, including Camp Evans. According to Carl, the DDUs at Camp Evans were probably never used for human shelter, but served as workshops for radar research and the handling of flammable/explosive materials. (A vintage photograph he found shows a Camp Evans worker pouring molten aluminum inside one of the units.)

In the little science museum, near the entrance to the camp, there’s a framed photograph that was taken on a sunny afternoon on July 18, 1945, only a month before Japan’s surrender. There are flags and stars-and-stripes bunting around a little stage and ranks of military personnel stand at attention while local townsfolk gather round in a crowd, listening to Colonel Victor A. Conrad present the Legion of Merit Medal to Captain Charles H. Vollum for his work on radar research. Just to the right, you can see at least six DDU’s in a cluster, with one lying right beneath a radar tower. Using Google Earth as my search tool, I was able to count at least ten circular concrete slabs that once supported other DDUs around the grounds, and if you add them together with the existing units, there was at one point a total of 28 DDUs at Camp Evans. Besides these, there’s at least one on the roof of the Myer Center in Fort Monmouth (about 12 miles away from Camp Evans), and another two–possibly more–at the Naval Ammunition Depot Earle in Monmouth County. Access to the Earle depot is highly restricted and I haven’t figured out a way to get in, yet. Among other hazardous ordinance, there are said to be a hundred or more nuclear warheads stored at the site.

DDUs at a U.S. Air Force base in North Africa, 1944 (Office of War Information Archives)

There were also three–and presumably more–at a US Air Force base in North Africa, as seen in photographs from the Office of War Information archives. No specific information is given about location and date, other than “somewhere in North Africa (1942-43)”. In the first photograph, three US pilots are standing in front of one of the units. The DDUs are perched on a freshly laid concrete base. They have conventional wooden doors and the porthole windows have been blackened out. (The foreground shows roughly turned-up earth, mud, shards of masonry. The sky is a matte gray.) The other photo was taken at a different angle and shows two of the units in profile while Colonel Carl Andrew “Tooey” Spaatz inspects the newly erected DDUs with two other officers. Spaatz was Commander of the Twelfth Air Force when it was stationed in North Africa, so this might possibly Tunisia, but it’s hard to say. Apart from all of the above, there have also been several undocumented, unverified sightings of other DDUs elsewhere in the mysterious hinterlands of New Jersey.

Soon after America’s entry into the war, Butler Manufacturing had to stop production of the DDUs. The U.S. government imposed limitations and all supplies of metal were consigned to weaponry–airplanes, tanks, bombs and guns–not housing. Fuller’s dream of an affordable, mass-produced dwelling unit was only temporarily delayed, however, as he soon started work on the Dymaxion Living Machine (better known as the “Wichita House,”) a circular, aluminum-clad house fabricated at the Beech Aircraft factory in Wichita, Kansas, hence the name.

Carl, my guide, points to the south, to the far side of a field at Camp Evans, near a wooded area, where there appear to be two more DDUs overgrown by knotweed and I walk into the field, into the nettles, and stick my head through a veil of creeping vines. These two units are even more crusty and patinated with age, even more haunting and beautiful than the first group, untouched since the closing of the base, left exactly as they were with original paint blistered and peeling off their metal walls as if burned by a torch. Nature has taken over, almost swallowing them whole and this gives them a sense of inverted time, as if they were ruins from the future rather than the past.

A shorter version of the DDU story was published in the New York Times on December 31, 2013: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/02/garden/war-shelters-short-lived-yet-living-on.html

A shorter version of the DDU story was published in the New York Times on December 31, 2013: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/02/garden/war-shelters-short-lived-yet-living-on.html

Pingback: ¿Sabes qué es la arquitectura de emergencia?

Stumbled upon these yesterday with absolutely no idea they were at Camp Evans. I’m an architectural historian who just happens to be chaperoning a youth service trip (Hurricane Sandy). The group is lodging at Camp Evans. I had quite a start when I went to park the car and saw the DDU. WOW.

In a 1953 aerial photo I can see at least 44 DDUs at Camp Evans.